15. 25 Years of the Good Friday Agreement: The Bicycle theory of change

A key lesson from negotiator Jonathan Powell: keeping moving is better than stopping, even if you find yourself going in the ‘wrong’ direction

How to nurture and build change when things are really challenging? That’s been a question for me over the years, and Solutions Focus is one very good way of doing it. And of course there are other ways and ideas too.

The last week has seen the 25th anniversary of the signing of the Good Friday/Belfast agreement which (more or less) saw an end to the Troubles, the nationalistic and sectarian violence afflicting Northern Ireland from the late 1960s into the 1990s. Some 3,500 died amidst bombings, riots, gang violence and recrimination attacks. The story of that sorry period is long and has many twists and turns. The fact that the Wikipedia page history of it starts in 1609 will give you an idea of how deeply wrought were (and in some cases still are) the divisions. The Troubles were a nightly feature of TV news when I was growing up; it seemed an intractable mess.

The Good Friday/Belfast Agreement

The agreement was forged over several years, with the British government of John Major having highly secret initial talks with the IRA (republican paramilitaries), who announced a cease fire in 1994. A key agreement between the UK and Irish governments was then struck, and a chain of talks led to US Senator George Mitchell brokering the ‘Mitchell Principles’ for how the talks would operate. After a great deal of ‘one-step-forward=two-steps-back’ toing and froing involving decommissioning of weapons, collapsed cease-fires, building of political consent on both sides and ‘we’ll jump if you’ll jump’ standoffs, momentum was seized by the incoming UK Labour government of Tony Blair in 1997.

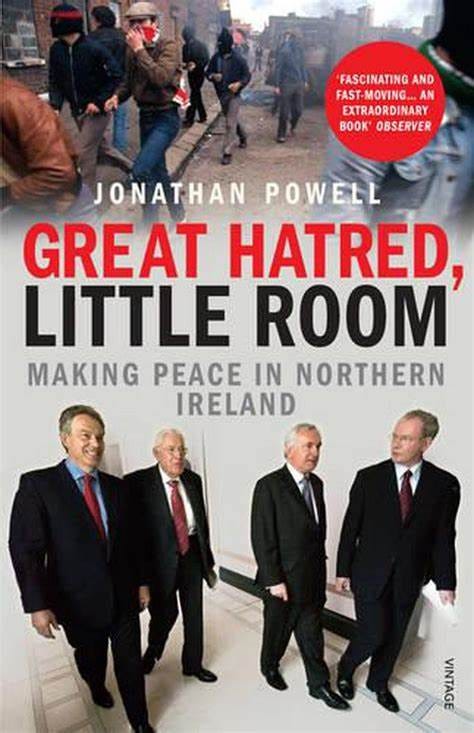

Jonathan Powell, Blair’s Chief Of Staff, played a central role in the year leading up to the agreement. Acting as Tony Blair’s representative he spend a great deal of time in talks with all the parties, often finding himself in tiny airless spaces surrounded by distrustful and angry people. His excellent book on this experience is entitled Great Hatred, Little Room ( a quote from Irish poet WB Yeats), summing up the experience both metaphorically (having little room to manoeuvre) as well as physically little room to move. It’s a gripping account of the process from right up at the sharp end. There was no guarantee of success at all; in fact, Powell frequently wondered whether it was possible at all. He says that Tony Blair kept him at it, insisting that movement was possible. And even after the Agreement was signed in April 1998, implementing it was (and continues to be) a challenge.

Jonathan Powell and the Bicycle Theory

I was lucky enough to see Powell speak when the book was published a decade or so after the events described. He is a very good speaker, was a diplomat prior to taking up his civil service role and subsequently founded Inter Mediate, a charity for negotiation and mediation. He came to the Cheltenham Literature Festival and told us about his Bicycle Theory of change in really tough situations.

Imagine riding a bike… and you get very slow and wobbly… the handlebars move from side to side as you struggle to maintain balance. Sometimes you may be pointing in the wrong direction. The Bicycle Theory says that it’s easier to keep going (and on the bike) than stop, when you fall off and have to get going again. Powell writes about it in Great Hatred, Little Room:

Throughout the negotiations, Tony Blair and I often discussed whether our belief that the problem of Northern Ireland had a solution was, in fact, ill-founded. There were certainly many occasions on which that belief was challenged. At first we thought that, having achieved the breakthrough of the Good Friday Agreement, all we had to do was implement it. But, by the end of 1998, it became clear it was not going to be that simple, and we were facing an endurance test. I would tell Tony that, no matter what, we had to keep things moving forward, like a bicycle. If we ever let the bicycle fall over, we would create a vacuum and that vacuum would be filled by violence. It was a precept we stuck with, and I don’t think that, deep down, either Tony or I ever really lost the belief that it could all be resolved eventually, if we were patient enough. By the end, we had realised peace was not an event but a process. (Great Hatred, Little Room. The Bodley Head, 2008, p5.)

Lessons from the Bicycle Theory

I think this idea is a brilliant insight. It’s so easy to grasp and viscerally relevant, particularly if you’ve been on a bike struggling over rough ground. Here are some of the key points I draw from it.

1. The importance of really believing that something IS possible in the end - even if you don’t know how. Otherwise you may find yourself giving up and thereby proving yourself right that it’s impossible! Solutions Focus hinges on this outlook. We have to assume that if our clients want to go in a particular direction in their lives, then it’s possible. How fast or slow, how far, under what circumstances… these are all to be discovered. And anyway, if something it clearly possible it’s not much of a challenge, is it? 😊

2. Any movement is useful – even if seems to be in the wrong direction. There’s a Solution Focused saying (coined by me, though I was trying to paraphrase Gregory Bateson at the time) that ‘change is happening all the time; our role is to notice useful change and amplify it’. In extremis, ANY change is useful to notice – it shows that things are not actually totally stuck. I have learned that some people are very skilled at overlooking change, even useful change, in their insistence that nothing is working or can work.

3. Think about tiny signs of progress – even if they haven’t happened yet. Considering and talking about what tiny signs of progress would be welcome is an excellent way to prepare yourself to be alert for them if they start to show up. And almost any movement can be construed as progress in a very stuck situation. Indeed, the whole SF approach started with awareness that things are never really stuck, there is always movement, one day is not completely the same as another (even if it feels like it) and these small differences matter.

4. Get talking and keep talking – even if it seems that you shouldn’t. The Good Friday Agreement started from the Major government talking to the IRA in the early 1990s, even though they’d said they would never ‘talk to terrorists’. Jonathan Powell has been very clear in recent years; you always end up having to talk. Setting down preconditions for the start of talks sounds like talking tough, but it actually just gets in the way; the discussion becomes about ‘whether to talk’ than about substantive discussion. I wrote here about how prime minister Theresa May made life difficult for herself in laying down preconditions about Brexit (Make agreements you WANT to keep, Steps To A Humanity Of Organisation #9). At present the UK Govt seems to have forgotten this wisdom in their dealings with trade unions, demanding they WITHDRAW their pay demands before talking. (Perhaps the Government thinks it gets brownie points from their supporters by NOT talking - and therefore making no progress. Funny old world.)

Practical help in very tough situations

Keeping the bicycle moving can mean making small moves that look almost insignificant – but they aren’t. Here are a few things I’ve used over the years. (This all applies equally to community building as to organisational change.)

Make sure there’s another meeting in the diary before you wind up

Agree a check-in sometime later (even if there seems to be no progress)

Think about ‘tiny signs’ that things were starting to move positively and look for them, nudge towards them, pick up on them

‘Go slow’ – sometimes it isn’t the right moment, wait and watch.

The idea of ‘Go Slow’ is another key part of SF practice. It’s often attributed to Insoo Kim Berg, co-founder of the SF approach to therapy with Steve de Shazer, though it goes back further than that. I think the Buddha might have had a very similar idea. ‘Going slow to go fast’ is another paradoxical idea (following last week’s piece on the Law Of Two Feet in Open Space). It encourages us to be patient, not to push too hard when the going is sticky, and that waiting and watching is itself an action. After all, if change IS happening all the time, then it’s there to be seen. And noticed. And talked about.

Conclusions

This time I’d like to give the last word to Jonathan Powell. Writing in 2008 at the end of his book, he says:

As I read back through the official files on Northern Ireland to write this book, there was one thing more than any other that kept jumping out at me, and that was the importance of having a functioning process and keeping it going regardless of the difficulties. Shimon Peres observed about the absence of process in the Middle East that ‘the good news is there is light at the end of the tunnel. The bad news is there is no tunnel.’ And that is what makes me believe so strongly in my bicycle theory. You have to keep the process moving forward, however slowly. Never let it fall over. So if there is one lesson to be drawn from the Northern Ireland negotiations, it is that there is no reason to believe that efforts to find peace will fail just because they have failed before. You have to keep the wheels turning. The road to success in Northern Ireland was littered with failures. And there is every reason to think that the search for peace can succeed in other places where the process has encountered problems – in Spain, in Turkey, in Sri Lanka, in the Middle East, in Afghanistan and even, in the longer term, with Islamic terrorism, if people are prepared to talk. (Great Hatred, Little Room, The Bodley Head, 2008, pp 321-322)

Dates and mates

You can hear Jonathan Powell reflecting on the events of 25 years ago and on the current (difficult) state of devolved democracy in Northern Ireland on this edition of the New Stateman podcast from a couple of weeks ago. Free to listen once you get past the first two minutes of ads.

I will be participating in the fourth BMI Dialogic OD Authors Salon on Monday 24 April 2023, 4pm UK time, online. Our theme is How do we support leaders in Generative Change processes?

Free to join, pre-registration essential. More details and booking here.

And… I am hosting a Village In The City podcast recording with Bella Kerr on the topic of Intergenerational Working on Wednesday 26 April 2023 at 4pm UK time. Bella is Intergenerational Development Officer at Generations Working Together. She is a very enthusiastic proponent not only of getting generations working together but of making that work high-quality and mutually useful.

This is a fascinating area where a lot of very useful difference can be made with a bit of planning and forethought. Bella will be talking about her experiences as well as giving us some top tips about how to get connection going between older and younger people. There will also be lots of resource signposting.

Reserve your place on the Zoom call now at https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/podcast-recording-bella-kerr-on-intergenerational-working-in-your-village-tickets-598319438547.

As a cyclist I can empathise with and understand this metaphor well. This is a super article, a pleasure to read and some valuable lessons.

Yes, spring is here, and people want to bike!

I'm looking forward to this time of year when we do long distance biking to Berlin but also biking downhill in the beautiful Swedish woods. Move, rest, balance, change.

The lessons from the Bicycle Theory and your key points are really brilliant!

(I also like that you are using the bike as an example when explaining SF in Alberts model:)