20. How competition and co-operation can work in harmony, not antagonistically

No matter what people might say, there is ALWAYS co-operation, even in the most competitive arenas. Finding ways to make co-operation and competition mutually supportive is key to our future.

Jenny and I are just back from a holiday in the Azores islands. This archipelago of nine volcanic islands in the mid-Atlantic is coming onto the tourist radar and it’s well worth a visit. There are rocks, lava flows and bubbling mud to be sure, but there are also lots of grassy paddocks for dairy and beef cattle. It turns out that the Azores’ secret export is high quality butter and cheese, and the steaks are excellent.

The vineyards of Pico

We also discovered a global landmark that I had no idea existed. On the island of Pico (named for its spectacular conical peak, a dormant volcano), there are vineyards. And no ordinary vineyards; these were planted centuries ago from soon after the islands were discovered by the Portuguese in the fifteenth century. (Yes, they were discovered – no previous inhabitation has ever been found.)

The enemy of everything on the Azores is the wind. The ’trade winds’ blow from west to east, with the islands in the firing line. This makes for a useful yachting harbour on nearby Faial island, but it also plays havoc with agriculture. The solution, for hundreds of years, has been to build walls around the vines. Built of black volcanic basalt rock using the dry stone principle (no mortar, just skilful construction, the walls are around three feet high. Amazingly, they are also only 6-10 feet apart! This leads to large stretches of landscape covered in walls, with vines interspersed. The walls not only protect the vines from the wind but also give heat radiating from the black rocks to help growth.

This landscape was recognised by UNESCO as early as 1986 (before Edinburgh!) and became a World Heritage Site in 2004. The Pico vineyards are mostly on the western side of the island, near the coast. The total area is 987 hectares or just under 10 square kilometres. (That’s a square just over 3km on each side, although it’s spread out along the coasts.) Amazingly, that small area contains thousands of kilometres of humanly built wall. It’s a superhuman achievement. The walls were originally built in the 15th-19th centuries and (of course) require a bit of repair every now and then. But the scale of it… it’s akin to the Pyramids.

Grapes into wine – the co-operative

The plots are very small and (of course) using machinery is such tight spaces is impossible. Harvesting the grapes and making the wines is a tough business anywhere, but it’s particularly challenging here. The solution, quite a common one in the wine industry, is a co-operative. There are many growers, often with very small plots of land. Do they compete? Yes, a bit. They want to grow the best grapes they can. And they co-operate too – with their co-operative for wine production.

This same model can be found in many other places around the world. The growers grow their grapes and sell them to the co-operative, who make the wine and market it. It’s a finely balanced combination. The growers get paid for quality (sugar levels, pH levels, fruit condition etc). And if you’re in with the co-operative, you’re in. A 2018 report on wine economics (free download) sets out how it works for the growers.

Despite many differences among these six wineries, there are also various common characteristics that might have been crucial for their success. First, being able to sell bottled wine under the cooperative’s brand name appears to be an important determinant (or indicator) of success; none of the six “Field Report wineries” sell bulk wine. Second, in order to avoid any moral hazard, where member growers only deliver inferior quality to the cooperative and sell their high-quality fruit on the market, members are required to deliver their entire production to the cooperative. Third, the cooperative influences the production process already in the vineyard by setting rules, conducting regular check-ups, and/or offer training sessions. Fourth, all successful cooperatives pay above-average prices to their growers.

Balancing competition and co-operation

Everywhere you look, there is a balance of co-operation and competition. Our place in Edinburgh used to be the headquarters of the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA). (They moved out in 2014 to modern offices and the building was converted back to residential.) The SWA is the trade body of the whisky industry in Scotland. All the distillery companies are members, and the association sets standards, keeps an eye on the law, promotes the industry around the world and protects against people who are claiming to sell Scotch whisky that’s never seen Scotland, never mind being whisky. It’s a hugely important part of the industry.

Do the distillers compete with each other? You bet they do! There have never been more different whiskies being launched, new distilleries arriving, new ‘expressions’ of malt whisky being marketed often to collectors (different ages, treatments, barrels…). And… they co-operate as well. The balance here is in a different place from the Pico wine makers, but it’s still there.

The Scotch Whisky industry is not unique. Everywhere you look there is co-operation going on. What do these trade bodies and other organisations do? Promote the interests of the whole industry, keep abreast of legal and other changes, set and enforce standard, ‘grow the pie’ of the market. Where is the co-operation in your industry or line of work?

Co-operation rules

Often competitors compete in a marketplace. BUT who makes sure the marketplace is offering a good forum? There are standards on advertising, on production, increasingly about environmental and sustainability, and so on. And, in places like the stock market, there are rules for participants about disclosure of accounts, notice of significant events, the identity of directors and their share dealings in the firm, and so on.

This works in sports as well. Manchester City won the English Premier League football tournament this week (and then lost to arch rivals Manchester United, which made no different to the tournament but helped the United fans feel better about it). Great rivals are hard to find but… they playing the same game to the same rules as part of the same competition. So this rivalry is within a much broader band of co-operation. Imagine for a moment that Manchester United were playing rugby – there’d be no rivalry with City at all! 😊

Tackling the huge issues – aligning competition and co-operation

The really big issues facing our society and our planet are not going to be tackled with competition alone. The climate emergency, resource depletion, rich/poor divide, clean water, education, energy supply; these are global issues (even if they translate differently in different places). These issues of sustainability are not going to be tackled by competition alone. Neither, I propose, are they going to be tackled solely co-operation at the level of governments.

What will make progress not only possible but inevitable (a phase borrowed from hypnotherapist Milton Erickson) is when competition and co-operation are aligned. Competition is fantastic for developing ideas, products and ways to do things. Co-operation is fantastic for setting the rules, aligning standards, building compatibility and making things work on a wide scale.

The internet as we know it today is a fine example. Tim Berners-Lee developed the first web software and website in the early 1990s. He could have made it a proprietary thing, but he didn’t; he made the work freely available and set up the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) in 1994. The Web is a hive of competition, but it wouldn’t work without common (and continually developing) standards. The whizziest new website won’t work without fitting in with these standards.

Solution Focus, co-operation and the Death of Resistance

I wrote here a few weeks ago on SF World Day about the 1984 Death of Resistance paper and why it’s such a key step along with way to Solution Focused (SF) working. Before this date, most therapists were using a ‘competition’ model of thinking where they had to outwit, defeat or beat their clients in the battle for ideas. The Death of Resistance marked a key and totally committed shift to working with co-operation. Not only is co-operating with clients essential, the initial task for the practitioner is to discover the client’s unique way of co-operating.

It seems to me that successful movement on the big challenges will come when these ways of co-operating can be found, constructed and brought into play. When ‘better’ for the planet and ‘better’ for the individual are pointing the same way, progress will be inevitable. In so many cases right now, these things are seen in opposition. What’s better for me is worse for the planet, and what’s good for the planet means me giving up something I like.

This is also true at the governmental level – too often it seems that countries hold back for fear of being disadvantaged (or not getting the advantages that others have already gained). I fear that exhorting people (and politicians) simply to do the right thing may be doomed. Rather, we might build platforms for co-operation that will engage and encourage competition in useful ways. Might Solution Focus have a role to play here? I think so.

Please like this post, comment and share. Thank you!

Dates and mates

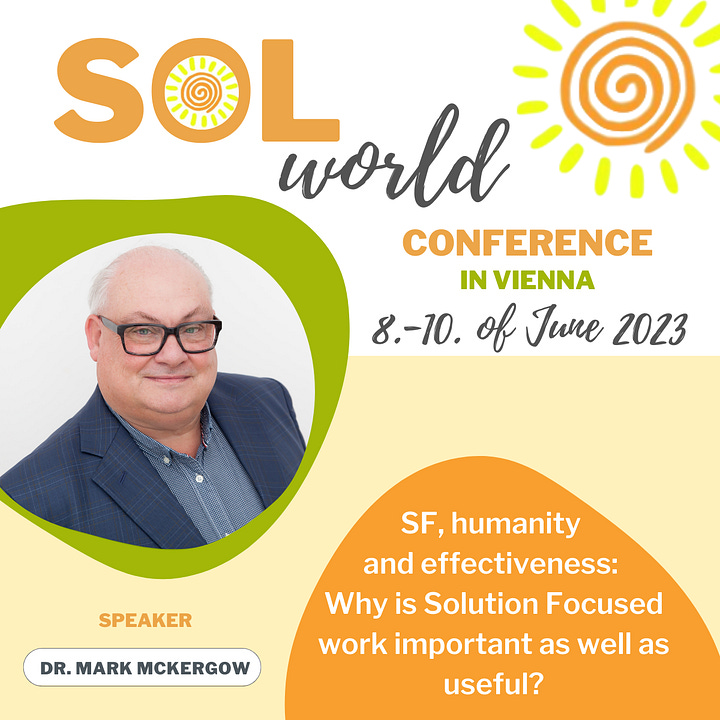

The SOLWorld 2023 conference of Solution Focused practitioners working in organisational and coaching settings is nearly here! Join me and many other SF people in Vienna, Austra on 8-10 June 2023. With some forty workshop presenters and speakers and a packed programme, this will be a memorable event. I am participating in three workshops - these two plus one on the SF Art Gallery in organisations with Susanne Burgstaller! Come and say hello - we can learn together.

Love this reminder that competition is not all bad. I see the balance in the competition being contained within a cooperation. In your example, the rules of the game containing the competition between teams, and the rules of the wine cooperative containing the individual wine makers. When the competition tries to contain cooperation (like in oligarchies and cartels), bad things happen...

Thanks Mark - fascinating insight into Azorean wine-growing. I note that they are low, shrub-like vines, as found in the hottest regions of Spain (La Mancha and Valdepeñas), not the classic hedges of Bordeaux or Burgundy, or the head-height vines more like you find in a greenhouse - or Rias Baizas of Galicia. As someone who has tried without great success to rebuild a dry-stone wall, those serried ranks of walls is indeed some thing quite extraordinary - the feat of building them is no doubt another example of collaboration between islanders. Small-holding, subsistence existence was probably less competitive then - the competition was really with nature to survive at all!