28. Preparing without planning: More about ‘Ant Country’

The future is emergent, not predictable… so what can we do if medium-term planning makes little sense?

Last week I wrote about the idea of taking a deep breath moment – pausing to reconsider and revised long-term hopes, goals and aspirations. I introduced the User’s Guide to the Future model (from my book 2014 book Host) and its concept of Ant Country – the middle future (not the immediate future or far horizon) for which it is impossible (or at least very ill-advised) to plan.

My friend and colleague Chris Corrigan in Canada picked up on the piece and I’ve had some positive reactions to Ant Country. This week I’ll explain how the idea came about, what it means and how to prepare for it. Yes, it’s possible to prepare for something without planning it – a key strand in developing humane and effective organisations.

The User’s Guide to the Future again

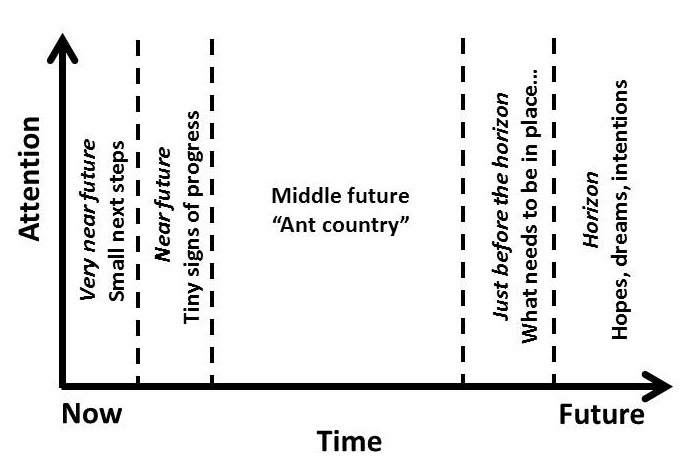

To recap, the User’s Guide to the Future framework addresses the way that not all parts of the future are equally useful, looking from today. We can split the future into three main zones – the far distant future, Ant Country and the near future. The far distant future, the horizon and just before it, is useful today because it’s the home of our hopes, goals and aspirations – the things we want to move towards. It helps set a direction. The near future is the home of small next steps and tiny signs of progress – again useful, the home of our actions (in the timescale of days or weeks) and the things to notice that would show progress in a useful direction. (By the way, thinking about what would be tiny signs of progress before deciding on next small steps is a very useful way to think widely but sharply about what to do.) And then there is Ant Country.

Ant Country

In between the near future and the distant future lies Ant Country, the middle future. It’s the least useful (in terms of making progress) of the User’s Guide zones; it’s too far away to plan for (because unexpected things will happen which will throw us off course) and not far away enough to be useful in setting direction. It is the zone of emergence.

I’ll be honest here. I didn’t invent the term Ant Country (though I may be the only person teaching it today). It comes from the book Figments Of Reality: The evolution of the curious mind by Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen, published in 1997. The book is a wide-ranging investigation of how inanimate matter can turn into complex creatures like us with rich inner worlds of mind and imagination, using the then-new science of complexity as a key theme. It was remarkable then, and it remains so.

Ian Stewart is a mathematician and Jack Cohen (who died in 2019) was a biologist, both with long research careers at top universities. A formidable partnership who valued entertainment and accessibility alongside scientific rigour (people after my own heart!), they were first drawn to complexity in the early 1990s with their first joint work The Collapse of Chaos: Discovering simplicity in a complex world (1994). Figments was described in a review in top science journal Nature as “a worthy successor to Gödel, Escher, Bach”. (If you don’t know Douglas Hofstadter’s masterpiece about self-reference and recursion, there’s still time… 😊.) I was lucky enough to get to know Jack Cohen a bit towards the end of his life; he wasn’t able to drive and so I would give him occasional lifts to Birmingham University.

The thesis of the book is that minds co-evolve with the world surrounding them, in an emergent way. This was a novel idea at the time, and in contrast to the reductionist hopes of many scientists that peering into the brain or discovering a ‘theory of everything’ would reveal the hidden secret to how we act, imagine, live and die. Drawing on complexity, Stewart and Cohen show in ways that stand up conceptually, mathematically and biologically how minds, brains, languages and societies must co-evolve in unpredictable and unexpected ways. It’s a tour de force, hailed as a breakthrough at the time and then sidelined because taking it seriously would put many scientists, biologists and philosophers out of work by showing that so many of the ‘big questions’ of life are wrongly conceived, muddled and unanswerable. I am reminded of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s investigations into language half a century earlier, which had a similar reaction in most quarters.

Co-evolution and emergence

Emergence is a key property of complex systems. The dictionary definition is that

emergence occurs when a complex entity has properties or behaviours that its parts do not have on their own, and emerge only when they interact in a wider whole.

This sounds a bit scary, but it’s actually a very everyday concept. For example, conversations are emergent. There is no ‘theory of language’ which can take the starting point of a conversation and predict what will be said even a moment later, let alone a day or a lifetime. Conversations (and language itself) emerge a step at a time, I say something, you say something, I say something else… and each step opens up another whole set of possible responses and next moves. Briefly, emergence is when there are more possibilities opened up than there are ways to decide which of them will actually happen. (In maths this is called an NP problem – my physics PhD touched on it and I may come back to it here another time.)

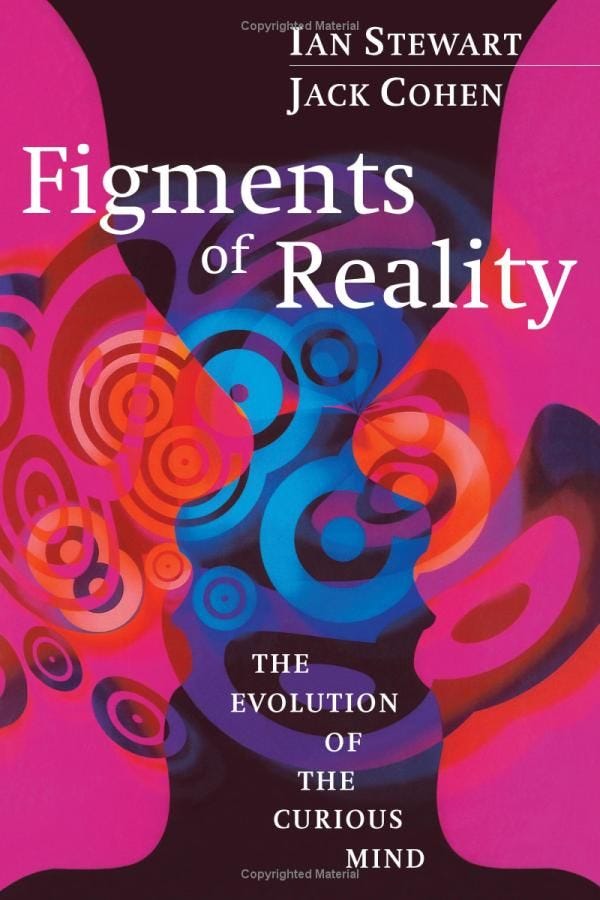

Suffice it to say that even simple emergent systems can show unexpected behaviour which is not predictable from the rules of the system (even if we know what they are). Stewart and Cohen use the term Ant Country to bridge the vast area between the beginnings and ends of games like Go and Othello. The first few moves can be planned and the last few moves (leading to a win for one player or the other) can be foreseen, the middle of the game (the vast majority) is not determinable by reductionist methods at the outset.

Note that this pattern – clearish starts and ends, fuzzy middle – can even be found in well-defined and closed games like chess. Top players research openings and endings but need to be flexible in the middle game period. And that’s just chess – 64 squares, 32 pieces, defined rules which don’t change, no chance of extra pieces arriving (yes, I know about pawns queening) let alone innovations like a piece which can move unlimited squares in any direction on a board which can change shape and has layers. Real life is much more like the latter, but even more complex and emergent – we have to make up the rules as we go along (as Wittgenstein put it).

What about the ant?

The ‘ant’ referred to in Ant Country is Langton’s Ant, a mathematical curio where very simple rules create complex and unpredictable behaviour. The ‘ant’ is a moving square on a grid which changes other squares from black to white. For more see the technical appendix at the end of this piece.

For me, the term ‘ant’ also connects the term to real-world phenomena like ant colonies and termite mounds, where the creatures self-organise and can respond to all kinds of upsets without a central plan, but with changing local interactions to (say) find a new route around a blocked path. In the same way that conversations emerge without a plan, the ants organise without a plan (but with some high-level results in mind).

What to do today about a future journey into Ant Country?

People (often mathematicians, scientists and engineers) used to think that with enough analysis in the present, it would be possible to predict the future. We couldn’t predict the future, they said, because there wasn’t enough data, analysis or indeed time. The arrival of chaos theory in the 1980s showed that there would never be enough data or time – tiny changes to apparently irrelevant things turned out to have dramatic effects on the future. In the 1990s complexity science started to show how even simple-looking systems could not be predicted owing to the effects of emergence. (Note that this is nothing to do with ‘quantum’ uncertainty, a term witheringly dispatched by Stewart and Cohen in Figments.)

Planning for exactly what will be happening in several months time is clearly nonsensical. However, we can prepare without detailed planning. Here are some practical ways to do exactly that.

Resources

My friend and colleague Peter Röhrig introduced this element into the User’s Guide framework when we presented it as a coaching tool at the SOLWorld conference in Budapest in 2019. There are lots of possible resources; not only money (though that can be very useful!) but previous experiences, ways to move things forward like Solution Focus (SF), co-operation with others, time to think (not being rushed), access to people and skills, and many more.

Relationships and trust

One of the learnings from the COVID-19 pandemic is that people who had already built up relationships with those who could support them were in a much better place at the start of the lockdowns than those who hadn’t. Not only making connections but developing trust so that things can happen quickly and without fuss is key. When we lead as hosts (rather than heroes), this is part of what we are doing – inviting and connecting with people to build relationships for the future.

Improvisational skills

Whether you’re a musician, an actor or a comedian, there are skills to learn that help you to improvise – to produce in the moment what would normally be carefully crafted and prepared. I’m a big fan of the Showstopper! group who improvise complete musicals with songs, characters, a story arc and even memorable tunes to hum as you leave the theatre. Is it written? No. Is it improvised? Yes, absolutely. Do they plan the performance? Do they prepare, work together, enjoy and learn about different musical styles, build trust – yes indeed, not just in the rehearsal room but in over 1000 performances so far.

What to notice

There may well be things which might come along in the future that would be worth noticing. Some of these might be very encouraging, things that will let you know you’re on the right track. Other things might be premonitions of disaster. It’s good to think in advance about both of these. In SF we are very keen to prepare to notice the useful and positive things. It’s also worth thinking about where the ‘waterline’ of your project is; holes below the waterline can sink the ship. As long as the ship is afloat there can be hope and forward movement. If the ship (metaphorically) sinks, that’s likely to be a more significant drawback (unless you have another ship moored somewhere – a useful resource!).

Skills with probes

Paul Z Jackson and I included the idea of working with ‘probes’ in the very first edition of The Solutions Focus book in 2002. It’s often misattributed to complexity guru Dave Snowden, but was actually introduced in this form by Shona Brown and Kathleen Eisenhardt in their 1998 book Competing On The Edge: Strategy As Structured Chaos. Remember how the USS Enterprise used to send out probes to test things like a planet’s atmosphere? This is a similar idea – try something small (maybe a new product or trial collaboration) that will explore possibilities and give useful learning, whether it ‘succeeds’ or not.

Conclusion

The idea of Ant Country is a very useful way of focusing attention where it can be properly useful (the near and far futures) and keeping it away from distractions and futile worrying (the middle future). Humane and effective organisations will be good at working with these distinctions; it’s good for the people, the organisation and the results when flexibility and focus come together.

Dates and mates

There are a couple of good options coming up to learn more about working with complexity:

My friends at the International Future Forum near Edinburgh are running their Competence in Complexity programme starting in November 2023. It includes two face-to-face intensives.

Chris Corrigan and Caitlin Frost have another of their Working with complexity inside and out online programmes starting in 2024.

Technical appendix – Langton’s Ant

Langton’s Ant is a very simple form of cellular automaton, a two-dimensional mathematical system that shows emergent properties form very simple rules. Briefly, the ‘ant’ follows these rules:

· At a white square, turn 90° clockwise, flip the colour of the square, move forward one unit

· At a black square, turn 90° counter-clockwise, flip the colour of the square, move forward one unit

This produces a random-looking pattern of black and whiter squares for about the first 10,000 iterations, at which point the ‘ant’ begins a stable pattern of behaviour building a linear ‘highway’ for itself. The ‘highway’ pattern is 104 moves long and repeats. The resulting pattern is shown here (the red dot is the ant’s position when the snapshot is taken):

There is no way of getting from the initial rules to the linear highway – no algorithm to reveal what’s going to happen. The calculation is simply impossible due to the many recursions and self-referential moves made by the ant interacting with its own previous path. And note that this is still true even if we know all the rules at the outset, and they don’t change. Some of you may have heard me speak about John Conway’s Game Of Life, a slightly more complicated cellular automaton which displays emergent behaviour even more quickly from a similar set-up.

If you want to play around with Langton’s Ant you can! There a good web implementation at

To see the ant in classic form, click on the settings cogwheel and change the rules to the original

(1, L, 1), (0, R, 1)

Then set it going! If you click the fast forward button in will speed up. Notice the moment when the linear ‘highway’ starts appearing and see if you can discover what makes it start.