39. Giving and sharing credit – a mirror which reflects and amplifies success

Acknowledging contributions is a key principle in humane and effective organisations.

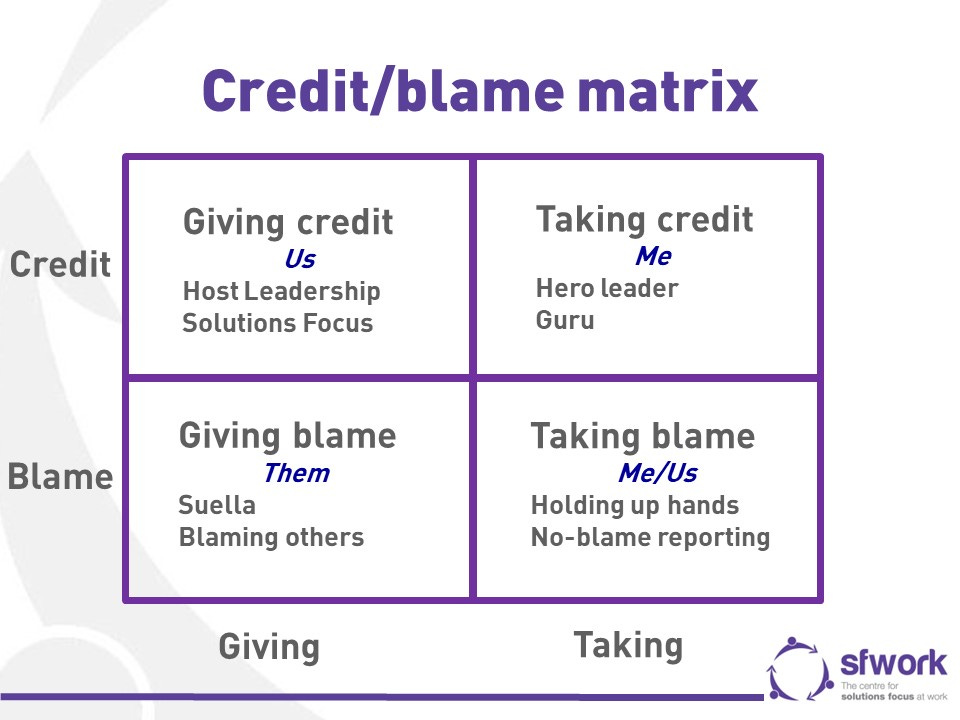

A couple of pieces ago I introduced the credit/blame matrix. This simple framework can help us to understand what’s going on when people give, or take, credit or blame. I’ve had some good feedback about the usefulness of this framework. Niklas Tiger, a senior manager at a Swedish software company, wrote in to say that he has seen top managers sometimes attempt to take the credit for something they had little to do with or (on the other hand) blame others for their failings. Who’d have thought it? :-) He summarised that hero leaders (try to) take credit and give blame, while host leaders generally give credit and take blame/responsibility. I heartily concur.

Trudy Graham wrote in from Australia to connect this with Jim Collins’ Level 5 Leadership in his book Good To Great. This combination of personal humility on the one hand and fierce professional resolve on the other was a key factor in the ‘great’ companies that Collins researched – very different to the alpha-male aggressive caricature of executive leadership predominating at that time. Writing in Harvard Business Review in 2001, Collins outlined the concept he called the Mirror and the Window:

Level 5 leaders, inherently humble, look out the window to apportion credit—even undue credit—to factors outside themselves. If they can’t find a specific person or event to give credit to, they credit good luck. At the same time, they look in the mirror to assign responsibility, never citing bad luck or external factors when things go poorly. Conversely, the comparison executives frequently looked out the window for factors to blame but preened in the mirror to credit themselves when things went well. (Jim Collins)

This time I’m going to look at how we as leaders or even just team players can give and share credit. It sounds a bit difficult but actually once we explore the reasons for doing it, it can become more natural and straightforward. I even have a framework to help us to do it (suitably acknowledged, as we’ll see later in this piece). But first – what is sharing credit and what’s it about?

The point of giving and sharing credit

Suppose that something has been a success. You were involved. Hurrah. Did you do it on your own? Well, I would say that the answer is always no. At a practical level there are always people who helped you, who taught you, who advised you, even who helped by not getting in the way. You climbed Everest solo without oxygen wearing boxing gloves and roller skates? Bravo you. But who taught you to ice climb, who got you to the bottom of the climb, where did your roller-skating expertise emerge from, who helped with food and supplies, who is now helping you get the word out?

At a more philosophical level it’s part of the interactional view (which I wrote about here) where everything – mental health, lifestyle, career, family, friendships and disasters – emerges through a network of interactions rather than being formed by something ‘inside’ you. Yes, of course people may say that they were ‘driven from inside’ or ‘drew on inner strengths’ or something, but that’s just an expression of how they feel about it – it doesn’t stand up to proper scrutiny. Solution Focused practice works from this interactional stance; we change the interactions and, well well well, the ‘inside’ feelings and emotions change too.

Acknowledging the others involved might sound as if it’s diminishing one’s own achievement. I think it actually amplifies it. It shows that you are a generous soul at heart, that you are aware of the part that others played in your success, and you are happy for that to be widely known. You ‘give it away’ but, IT manager Niklas Tiger pointed out:

Any credit given tends to multiply and bounce back on the one giving. And any credit taken tends to fade away in the process. Much the same happens while giving and taking blame. 😁

Let’s look at some fields where giving credit is a part of how things work, sometimes for ages and sometimes as a recent development. Then we’ll see how to do it.

Movies – the growth of the credit roll

Many people would say that Casablanca is one of the greatest movies ever made. Directed by Michael Curtiz in 1942 and starting Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, it’s an (utterly fictitious) story of love and escape through Africa in World War 2. If you haven’t seen it, treat yourself – it’s a marvellous piece of story-telling and performance. When I first saw it on the big screen (around 1994, at a special showing to mark the re-opening of a neighbourhood cinema in Bristol), Jenny and I made up 40% of the audience. The other 60% were three old ladies who audibly swooned when Bogart made his appearance. Movies from your youth can get you like that.

Anyway, take a look at the opening of Casablanca today. There are the stars, the title, key other actors, a few pages of the main creatives (screenplay, photography, special effects, music etc) and then we’re into the setup, a fiction about how refugees made their way across Europe and along the north African coast to Casablanca in the hope of getting a boat to the new world and escape the war. Just over a minute is enough to give us all that information and get on with the movie. A total of 39 people are named. That’s it. There are no closing credits; the final scene dissolves into a caption saying, ‘The End’.

Compare that with today. Big productions can have thousands of names on screen, particularly if there’s a lot of CGI involved. The later Harry Potter films have credit rolls lasting up to 15 minutes; so long, indeed, that an extra short scene is left until the very end in a bid to keep people watching. I first noticed the phenomenon of long credits when I watched The Blues Brothers in 1980 and couldn’t believe the list of stunt people!

What’s changed since Casablanca? First the credits are now almost all at the end; with so many to name it would be hopeless to try to do it at the start. Second, of course, everyone now gets a mention. Back in the day all the people employed by the studio to do grunt-work didn’t get credited, they were just doing their jobs. My movie-connected chum and Introverted Presenter author Richard Tierney confirms that nowadays each movie is a new project, even if lots of the people involved are often working with the same studio company for film after film. And guess what? Their contracts will usually include that they get a credit mention, and they’ll work for less money if they get one, rather than being anonymous. Even the people running the food truck want to be mentioned.

There are all sorts of good reasons for this. Not least, as most of the people making the movie are independent professionals, the credits are their CV and reputation for future employment. This is so important, particularly for young emerging talent, that it’s not unknown for them to be asked to work for free in order to get a credit (a disgraceful practice, but one which shows the value of being associated publicly with success). To be fair, there are also examples of directors taking their name OFF a movie which they see as sub-standard; Alan Smithee is one such pseudonym-for-disaster.

Sharing credit: a three-part riff

There are all kinds of ways to share credit with others. This is not only good for them, it also reflects back on the one giving the credit. Not only are you saying that there has been some success, and that you played a (small?) part in it, but by shining a light on the others involved you are also demonstrating that you noticed them and you are happy for that to be known. Everyone’s a winner.

I’d like to share a favourite way to conversationally share credit. It came originally from Finnish Solution Focus author and speaker Ben Furman, who wrote it in an email to the SOLUTIONS-L listsever (now the SOLWorldList Google group where people talk about using SF in workplace settings) in 2002. It might have disappeared at that point (even though all the list postings are archived and remain accessible), but long-term list member Klaus Schenck remembered it in 2009 and brought it to the fore once again. Some of you may have been to my trainings over the years where I have taught a ‘three-part riff’ for platform building; this is a cousin to that.

Giving credit and acknowledgement: The Triple Praise (by Ben Furman)

I like to teach people how to pay more attention to small successes. In order to do that you have to help your colleagues to pay attention to their own successes. You do this by creating a culture where everybody feels free to report small successes to each other such as "Wow! I just managed to open Microsoft Windows!" or whatever. In order for people to want to broadcast small successes they have to be relatively sure that other people will respond in some supportive way and to be willing to share the joy of success.

I then ask people to make pairs. Each one is to tell their partner some small success that happened recently. They are then to respond to their partner’s success with what I call a "TRIPLE". I say “Oh, you don't know what a triple is? C'mon everybody should know what a triple is. You need to use the triple frequently not only to communicate with your work mates but also to

communicate with your children and even your spouse." That gets people curious to learn about this odd concept TRIPLE that they of course never heard of (because no such thing exists, I just made it up).

The name triple is short for the scientific concept known as "The Triple Praise" (I am speaking tongue in cheek). The triple praise consists of three elements. The first element is called "The Exclamation of Wonder" (EoW). Usually it is a vocalisation that includes the word "Wow!". The second part of the triple praise is called (in scientific circles) the "Statement of Difficulty" (SoD). That means that after the exclamation of wonder you make a statement about how difficult, or hard it is to succeed with something like that. My favourite SoD goes like this: "That's not easy!" but you can test all kinds of variations such as "I would not have been able to do that!" or "Not everybody can do that!" etc.

The final part of the famous triple praise is a question, known as the Interrogation of Credit (IoC). It is a simple questions that seeks to find the reason for the success in question. My favourite phrasing of the IoC question is: "How did you do that?" but other options are available for the

creative TRIPLIST.

The person in the exercise who has reported the success and has now had the experience of being the recipient of the TRIPLE is now to respond to the IoC question in a specific way known in the Science of Solutions (SoS) as "SHARING CREDIT". This means that they are to have an attack of generosity and to share credit for their success with whoever comes to their mind. In

effect they are to say something like: "I'd never have succeeded with this if so and so had not have helped me (or supported me or whatever)." The exercise, however, does not end here. It has a final part. And the final part is called BACKCREDITATION. Yes, you read correctly. Not accreditation but backcreditation. Backcreditation is a new scientific term that refers to the act of giving credit back to the person whom it belongs. There are many phrases you can use to do backcreditation. My favourite one is: "That's kind of you to thank (him/her/them) but I am sure that you yourself played some part in it too!".

The recipient of the backcreditation is coached to respond to it in a specific way, by saying thank you or, here in Europe, by acting shy and smiling kindly at the same time.

Enjoy the exercise. Try not to explain people what it is all about. Instead ask them to make their own sense of it and be amazed at how wise they are in understanding the deep meaning of this extraordinary scientific exercise.

The exercise is in fact a serious exercise but I tried to present it here with a humorous tone of voice (very difficult in e-mail messages) to give you an idea of how I like to instil some humour when I present exercises to people.

Ben Furman (in 2002)

Conclusion

I love all of this exercise from Ben, and in particular the way in which he sets it out so that someone else sets out to notice that something has gone well, and the one who has succeeded is drawn in to sharing the credit and success. And of course, it can work the other way too, where success sharing and backcreditation (great word!) can come along anyway.

We’re coming toward December which is a good time for drawing together the events and successes of the year. Why not think about your own successes in 2023 and then drop a line to those who’ve helped you to acknowledge them and say thank you? You never know, they might even write back with some backcreditation. (Your chances of this may be enhanced if you share this post first!) 😊

Dates and Mates

Ben Furman is still very much alive and with us. Check out his books and work here.

My good friends at BRIEF in London posted a short piece last month crediting Ben for ideas on sharing credit, which includes a lovely solo 30 minute exercise about considering the five people who have supported the emergence of the ‘best you’. Check it out (and even do it) here.

I am thrilled to be the guest on the latest podcast in Dr Paul Scheele’s MINDTRX series. We talk about how to pick your way forward in a complex world that’s always emerging in surprising ways. Solutions Focus and Host Leadership feature. It’s free to listen.