65. Jazz as a metaphor for leadership

The explicit combination of structure and freedom offers a fine way to encapsulate how work can involve personal expression and higher-level organisation.

In this last piece in the present series (don’t despair, I’ll be back in September!), I’m looking forward to a jazzy summer by looking at how jazz groups work in organisational terms and how there are many useful lessons for those of us seeking to organise in humane and effective ways.

Music leadership metaphors

There are various ways to look at how leadership works in musical performance. Perhaps the most familiar is the orchestra conductor, who stands at the front waving their arms, but doesn’t actually play any instrument at all. Some would say their ‘instrument’ is the entire orchestra. There’s a superb TED talk by Itay Talgam about the different styles of great conductors and the implications for their leadership.

However, the orchestra conductor model seems to me to imply a kind of dictatorship (even if possibly a benevolent one). The conductor sets the tone, speed, style and the orchestra must follow. It’s possible that there may be discussions about these things beforehand, but when push comes to shove the conductor leads and the players follow.

Another possibility is the big-band leader. Think of Glenn Miller and his band, famous during World War II. Miller stands out front moving his finger to and fro in a conducting-ish fashion – but he’s also holding a trombone, on which he plays solos and sometimes joins in with the band. Here the leader is clearly also one of the players as well as the top dog. Here he is with the band in a colourised movie scene playing the role perfectly in In The Mood.

There were good reasons for Miller and his ilk to stand out front. They were the named star band leaders, people wanted to see them. It was not uncommon for patrons to request tunes in a dance setting, and making the band leader visible and accessible gave them a way to do it. In truth, though, this isn’t so much about musical leadership. If the band leader stepped away for a moment, everything would carry on regardless.

If we look at a smaller jazz group, a new form of leading emerges. There is no visible leader out front. Everyone is a member of the group and is playing an instrument. There is (usually) also no sheet music. But that doesn’t mean it’s total chaos; there is clearly a theme, a speed, a key, a feel shared between the musicians. People are improvising and yet somehow it all fits together.

Here’s an example; Gary Smulyan and Joe Magnarelli playing Thad Jones’ tune Three In One, live at Troy Jazz in New York state on 18 November 2023. Smulyan and Magnarelli are both prominent players in the New York area, and they’ve been booked by the club who have provided a rhythm section of piano, bass and drums. It’s likely that these five have never played together before – but they know how to make it work over 12 minutes of Thad Jones’ tune Three And One. (I’ve been playing baritone sax recently and am a big fan of Gary Smulyan, a little guy who is so adept on the big horn.)

I’ve been playing this kind of music for nearly fifty years on and off. I am struck by how many non-musicians appreciate the music but don’t know how it works in organisational terms. So this time, I am going to share that and make connections with leading in other settings.

Structure and freedom

Jazz is basically an improvisational artform – people are mostly deciding what notes to play as the piece develops. However, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t structures in place to guide and support the music. The space within the structure is open for freedom, interpretation, personal choice and fluidity.

Some of these structures are quite tightly defined and others are looser. There is usually an agreed musical style (eg swing, bebop, mainstream, trad, funk), and then a theme which gives a musical key and a series of chords underpinning the tune. The sheet music, if there is any, will give just this information. There won’t be a piano score with both hands laid out, there won’t be anything to tell the bass player or drummer what to do – everyone starts with the same framework.

There might be an introduction from one of the musicians, and then usually the theme is played by everyone. This lets all present know what we’re doing, sets it up and allows the audience to hear the starting point if they don’t already know it. (There is a great tradition in jazz for re-using popular tunes and chord sequences, so the chords may be familiar even if the tune isn’t.) There is then a series of solos and interplay sections which are not usually predefined; the musicians feel their way through until finally everyone comes back together to play the original melody again at the end. And this happens in different ways for each number during the performance.

But if there’s no conductor, how do the musicians know what to do? They have a common vocabulary and know how to speak it together. Just like people who don’t know each other having a conversation, they listen and respond. It’s the quality of the listening that goes a long way to determine how interesting the show will be. For me, this sense of possibility is key to my enjoyment of the music, as a performer and as a listener.

There are lots of leadership lessons from this way of working. I must acknowledge the work of organisation development and Appreciative Inquiry professor (and jazz pianist) Frank Barrett, whose book Yes To The Mess: Surprising Lessons from Jazz (Harvard Business Press, 2012), is a seminal work, well worth reading.

For today, I want to focus on three key points.

Everyone’s role is to do their job and support the others

Leadership passes around the group

When you’re not leading, there is still plenty to do

Everyone’s role is to do their job and support the others

Everyone has something to do in a jazz group. The horn players solo and usually join in the melody statements. The piano or guitar adds chords to mark out the harmonies. The bass (to some people’s surprise) is the key time setter in most modern jazz, while the drums add rhythmic variation, swing and accents. And you all do it together. Everyone is listening all the time, seeking to make their contributions in ways that build and enhance the whole. And everyone matters. I remember British jazz icon Humphrey Lyttelton always gave out full musician listings on his weekly BBC radio show; people complained at the time it took, but he said it mattered that it was (for example) Barrett Deems on drums on this Louis Armstrong track and it was his job to tell us. He was right.

It’s no good hearing the time counted in and, thinking you know better, starting off at a different speed. It’s useless to start your solo in the middle of someone else’s to try to elbow them out of the way. It would be crass to start playing a different tune/structure that didn’t fit, in an attempt to show how clever you are (it won’t). In the moments of the performance everything should fit together and flow (and there are SO many ways to do that). We’re trying to create something new and worthwhile, without talking about it, which makes good use of the assembled talent. And everyone has to put their talent at the service of the other group members; nobody will thank you for being too loud, putting yourself first all the time, or fiddling around while someone else is trying to take their turn.

Leadership passes around the group

Usually one person will be tasked with counting the group in for the next number. This is a significant responsibility at the moment, but once done it’s done. Everyone gets themselves into the groove with the melody statement, fitting together. And then it’s time for the first solo. In my experience, this is not agreed beforehand. By eye contact and gesture, someone will step forward or (more likely) step back to offer the space to someone else.

Look at the Gary Smulyan/Joe Magnarelli video above. At the end of the tune statement (50 seconds in), Smulyan turns and walks head-down off the stage, firmly passing the baton to Magnarelli who is straight into the first solo. At the end of the solo (3:06), Magnarelli turns as his final notes ring out and Smulyan picks up from off-stage. He walks to the mic to build his solo. He stops at 6:35 and walks off, leaving Ian Macdonald on piano to pick up. (Note that piano and bass have chord sheets, as this is a one-off group for a single show and they aren’t totally familiar with the specifics of this piece.) At 9:02 the piano solo ends and Magnarelli picks up from off-stage on trumpet. He plays eight bars and stops. The bass player plays a few more notes and realises we’re moving into a drum break section, so stops. The drummer (Joe Barna) picks up and does eight bars (this kind of interplay is part of the vocabulary. The horns continue to swap eight bar sections with the drums. Smulyan’s final eight is a quote from another tune (10:22) – are we going to move into it? No, Barna recognises the quote and phrases his last solo section accordingly. Magnarelli point at bass player Jason Emmond (10:35), who take his solo incorporating part of the melody. And then it’s everyone in for the closing theme and ending (signalled by Smulyan turning to Barna to stop, giving a short coda section).

None of this (I suspect) was pre-determined beforehand. The musicians are all experienced and know the kind of thing they’ll be doing, but not the precise order or timings. When someone takes a solo, the rest fall back to support. The order of soloing emerges as the number goes along.

When you’re not leading, there is still plenty to do

When someone solos, the others support in other ways. Look at how Barna is beaming from behind his drumkit, and how the occasional yelp of encouragement can be heard. It looks like Magnarelli is the closest to a formal ‘leader’ but even he steps back and allow other things to happen. And of course the other musicians keep going to support the soloist – Barna drops out the drums when the bass is soloing, for example. Everyone is engaged all the time – even when the horns are off-stage in their chairs they are ready to step forward when needed.

Some of you may be noticing the ‘step forward/step back’ idea from my work on Host Leadership coming in here, and you’d be right to do so. Even when the leader is ‘stepped back’ they are still participating in support of those currently in front, observing how it’s going and getting ready to step in again when the time is right.

Looking forward to a jazzy summer

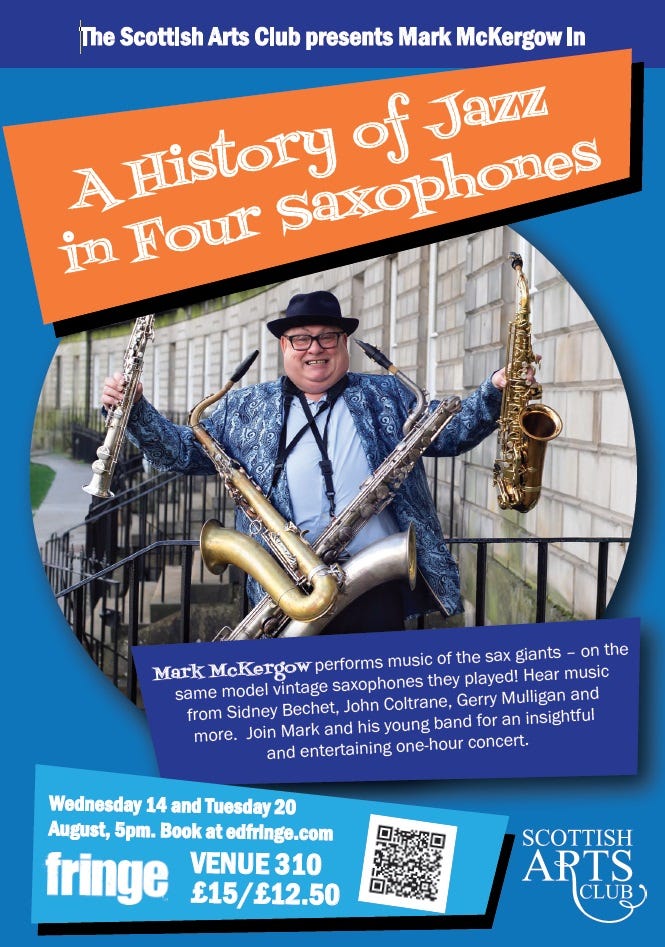

I will be putting all this into practice in my first small-group jazz shows for decades. A History of Jazz in Four Saxophones (14 and 20 August, 5pm, Scottish Arts Club) is my offering for the Edinburgh Fringe festival. I’ll be performing music by the jazz greats – on the same kind of vintage saxophones they used! There will be music from Sidney Bechet, Coleman Hawkins, Gerry Mulligan and more. I will be joined by a wonderful young trio of the some of the best young jazz musicians in Scotland – Ewan Johnstone (piano), Timmy Allan (bass) and Roan Anderson (drums). It’s all going to be great!

This is the last Steps To A Humanity Of Organisation for this series. I am taking a break from weekly writing for July and August. We’ll be back on Wednesday 4 September with more about how to organise in ways that are both humane AND effective.

Postscript

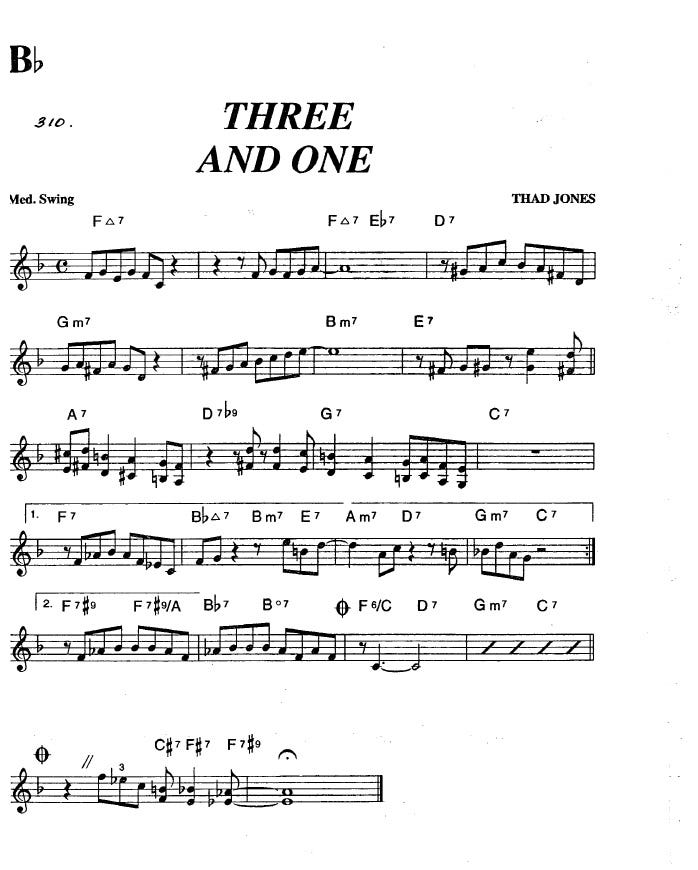

I've had a question about what the sheet music looks like for this kind of improvised performance. Here is the Bb part (trumpet) for this tune. You'll see it has the melody line and the chorts to use as a basis for improvising.

Dates and Mates

I have been reviewing jazz albums and concerts for UK Jazz News (formerly London Jazz News) since 2014 and have now done 150 reviews. There’s a list of them all here which you can read and get to each review. If you want to read more of my writing over the summer, this is an excellent way to do it! :-) The 151st review, fittingly of Gary Smulyan’s latest album, will be out on Friday morning at https://londonjazznews.com.

Looking ahead to the autumn/fall, I will be running the first Solutions Focus Business Professional course for ages. If you’re a coach, consultant or in-house change leader and would love to learn how to do this kind of effective, energising and engaging work, here’s your chance! I will be leading the first Solutions Focus Business Professional course for a while, starting Sunday 27 October 2024.

It’s a 16 week certificate course offered with the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, the home of online SF training since Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg were doing it in the 2000’s. It’s a great combination of readings, reflections, online discussions, pairs exercises, coaching practice and a project. Most of the work can be done ‘asychronously’, to fit in with your own life. And I’m with you every step of the way. This will be the only SFBP course this year. Yes, it’s an investment but everyone who does it says it’s totally transformational for their work. Places are limited. Click here for more.