83. One Small Step – the rise and rise of the parkrun movement

parkrun provides an excellent example of how to start something small and build while maintaining key values – very solution focused!

As regular readers will know, I’m very keen on the power of small actions and encouraging ripples to spread. That’s how we can build wide-scale change without complicated and expensive plans. This time I’m going to describe one such process which really has gone from one small step into a global movement; parkrun. With over 2000 free and inclusive 5k runs every Saturday morning in cities all over the world and hundreds of thousands of participants, this really is a worldwide phenomenon.

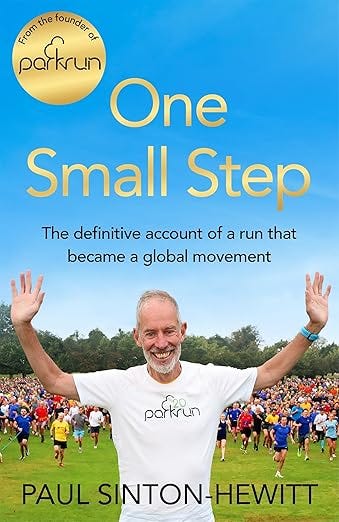

They celebrated 20 years last year and the founder, Paul Sinton-Hewitt, has just published a very good book about his life before and after parkrun. It’s called (what else…) One Small Step. I’ll be sharing some highlights as well as things that strike me as significant, and reflecting on what I think has made it work so well.

How it started

Paul Sinton-Hewitt was born in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and grew up in South Africa in the 1960s, the youngest of three children. He didn’t have the happiest of childhoods (British understatement!), went through boarding school and national service and moved to the UK to work as an IT consultant in 1995 following the collapse of his marriage. He was also unlucky with relationships – divorced with two children and unable (or unwilling) commit to new partners. Running had given him solace through it all; he had joined running clubs, become mates with one of South Africa’s top endurance athletes and recorded a very respectable 2 hour 36 minutes for a marathon.

Paul found himself injured after a training run. He had hoped to be back running within weeks, but the specialist told him it would be more like years. His life seemed empty without the companionship of his running club colleagues. He had participated in ‘time trials’ in South Africa – running against the clock rather then the other competitors and decided that this format might go well in the UK, even if it was unknown (running clubs run races!). So, in conversation with his clubmates he decided to host a weekly time trial run in Bushy Park, south London. It would be free to enter, everyone would be times, and crucially it would be ‘a run, not a race’.

Remember that Paul himself is seriously injured at this point. He can’t run. But he wants to be with runners and enjoy the company. He is hosting the event, the runners and the volunteers.

The very first Bushy Park Time Trial (as it was known at first) happened on Saturday 2 October 2004 at 9am. 13 runners showed up, most from running clubs, and five volunteers helped to manage the timing and finish tokens (handmade by Paul himself from steel washers) which matched the times to the people. (This system, slightly revised, is still in use today.) Paul’s newish girlfriend Jo was one of the runners. Afterwards they all went to the park café for coffee and cake. Paul promised to be there next week and every week.

I think that part of the success of parkrun comes from the fact that Paul was an IT consultant. Even at the very first event, he had devised a system which would record the times of each runner, by name, to be shared afterwards. That way everyone could see how their performance compared to previous runs, and whether they’d managed a personal best (PB).

The run grew and grew. That year Christmas Day and New Year's Day were both on Saturdays. There was some surprise that Paul was keeping his promise to be there every week, and a good crowd started their Christmas Day with a run before returning to their families. By the start of 2006 over 100 people were showing up, and that number had tripled a year later. But there was still only the one Bushy Park time trial.

The movement develops

Towards the end of 2006 some of the runners wanted to start another run on Wimbledon Common (not that far away). Paul was reluctant at first, figuring he could only be in one place at a time. However, the format was robust and so he was convinced to allow a couple of trusted friends to take a lead. He also tweaked his computer system to allow the results of both runs to be uploaded and accessed together; this meant that whichever run people joined, their times would be recorded. The first Wimbledon Common time trial ran with 51 runners and two volunteers. The next week there were 56 runners and four volunteers – a sign of steady momentum. Paul helped at the first two Wimbledon events (rather than taking a lead) and could see how it was all working.

At around this time some of the initial runners were approaching their 100th run (the computer system making it easy to keep track of this information). Paul had black fleece jackets made up with ‘100’ on the back, matching his own wear and emblazoned with BPTT (Bushy Park Time Trial) on the front. The ceremonial handing-over of the jackets added to the community feel. Paul realised that organising the time trials had helped him through a difficult time. Other people were coming forward to start their own runs, and by the end of 2007 there were seven events around England with 800 runners every week. A year later that had grown to 15 event and 1500 runners including in Wales and Scotland. Yes, there were financial costs and Paul was able to keep going with contributions from start-up groups. But the burden was growing and he needed to start getting sponsorship. He set up a company, UK Time Trials Ltd.

Finding ‘parkrun’

Some of Paul’s colleagues didn’t think that UK Time Trials was the catchiest name. Maybe some else might encourage more people to come to their local park on a Saturday morning. One suggested Park Run. At that time Paul was in conversations with Nike about sponsorship and thoughts turned to the name. One of the Nike marketing people suggested making it one word, Parkrun. Then they proposed removing the initial capital and italicising it, giving parkrun. And so it has remained; it does what it says on the tin!

By this time international visitors were discovering parkrun while in the UK and wanted to carry on when they returned home. Pauls friends back in Zimbabwe started a run, and Denmark was the first other European country to establish parkrun. There are now parkruns in 22 countries, from Eswatini to Malaysia.

Paul found himself looking for even more support in the UK and talked to running legend David Bedford, race director of the London Marathon and fully engaged in the club running scene. Bedford was sceptical (to say the least) about how such an operation could put on free runs all over the country – no one else was doing that at all. Paul found himself painting a picture of a pyramid – top-class competitors at the top, club runners and enthusiastic amateurs in the middle. Parkrun provided the (missing) bottom level; the foundation where people started running 5k in the park for fitness, activity and social connection. And, of course, some of those people would begin to work their way up the pyramid and even be future Olympic champions. Bedford saw the point immediately and offered £50,000 support from the London Marathon.

This point of an inclusive foundation level is really key. Paul is pleased when someone sets a new record time for a parkrun (currently 13 minutes 44 seconds by Nick Griggs in Victoria Park, Belfast in 2024). But he says he is even more pleased when someone posts the slowest time (currently something over one hour) – because that shows that people are being drawn to have a go at 5k and managing to do it. Indeed, they have recently been promoting the idea of parkwalk, where people deliberately set out to walk the 5k course along with the Tail Walker who always brings up the rear at every event.

Challenges along the way

In the end Paul gave up his IT consulting job and went full time for parkrun. His vision of doing things right and all will be well has been borne out. There have been challenges along the way for sure. What about kids? To start with they ran along with everyone else, but there were issues around keeping things safe. Junior parkrun started in 2010 – open to those aged 4-14, on a Sunday morning and over 2k distance (so the parents could still run their own run on a Saturday). One local authority wanted to charge parkrun, and in the end the organisers stopped that particular event rather than setting a precedent – it would have made offering the event for free much more difficult.

Now in 2025 there are over 2000 parkruns every week around the world, plus 482 junior parkruns, 365,000 parkrunners plus 35,000 junior parkrunners, and 46,000 volunteers in total per week. What a wonderful success from the initial time trial for 13 runners in 2004. And Paul is still with Jo.

Reflections

I think this is a marvellous story about how a good idea can grow organically. What helped it to work?

Paul Sinton-Hewitt knew what he was doing from the outset. He’d experienced time trials before (overseas) and knew how to organise such an event, including the timing and IT system

It’s a very clear offer – a 5k run (not a race!) at the same time and place every week

paul committed to doing it this week, next week and every week ‘for ever’. That really gives confidence to those turning up

Paul wasn’t running himself. His injuries meant that he had to focus on hosting the event rather than participating. He was therefore free to greet the first home – and the last

He set some key parameters from the very start – it should be free and inclusive all the way. This made some later decisions (for example about whether to pay to use the park) much more straightforward

Paul’s IT background to create and upgrade the earliest systems really paid off. The parkrun system is now worldwide and logs every person, every run and every time. Which also makes marking the 25th, 50th, 100th runs very straightforward

He wasn’t in a rush to expand. The second parkrun started over two years after the first. Expansion wasn’t the driver, but was rather a side-effect of having something that people wanted to be part of as participants and as volunteers

In the end, the social aspect of parkrun is key. In many parts of the world ‘jogging’ (as it was then called) was seen as a solitary activity. Parkrun offered the chance to run and exercise in a group setting with coffee, cake and chat afterwards (for those wishing to partake).

Conclusions

Paul Sinton-Hewitt is a very fine example of someone who had a great idea and has stuck with it. The way he has nurtured parkrun is inspirational. I volunteer myself at our local junior parkrun and can attest to the joyous and inclusive nature of the event, the way it encourages participation and offers a chance to get out and about on a weekend morning. And, of course, Paul is a fine example of a host leader.

Dates and mates

By the time you read this I’ll be on the way to the SOLWorld 2025 conference in Mechelen, Belgium. The theme of the event is ‘In Good Company’ and I’m looking forward to seeing friends old and new, giving a workshop on Writing SF, joining Alex Steele of Improwise for a session on Solution Focus and jazz, and catching up with lots of great people. It’s a sell out and there is a waiting list. We’ve come a long way from SOL 2002 in Bristol - over 60 SOLWorld events later. You can see the full list on the new SOLWorld website at http://solworld.org.

Very inspiring! What people want but know not yet how...I want to find something that i can start.