86. Better Decisions + summer treats

A classic article and some fun extras for my last post before the summer break

This is the last article on Steps To A Humanity Of Organisation before the summer break, so I’m changing things around and putting the last section (‘Dates and Mates’) first for once. There’s information about my Edinburgh Fringe gigs plus a piece of original work I did a little while ago about aviation pioneer Louis Bleroit’s efforts to develop fast boats on the River Seine before the first World War.

Below that you’ll find my article on Better Decision Making with Solution Focused Coaching, originally published in 2016 and featured on the SFiO website. I put together 10 different ways of using SF to help making tough decisions, none of which is about trying to predict the future (which is the usual default method, envisaging the possible results).

We’ll be back in September with more conversations about how to organise humanely AND effectively. Have a great summer.

Mark’s jazz gigs at the Edinburgh Fringe festival 2025

I have two different shows this year, with two performances of each.

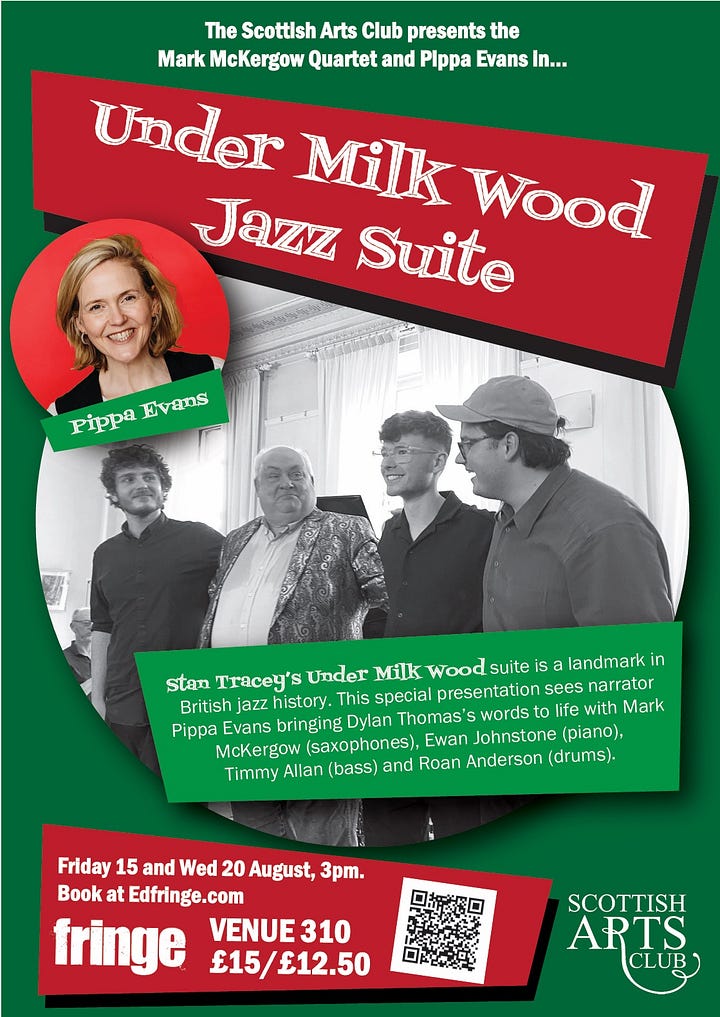

Under Milk Wood Jazz Suite sees me and my amazing quartet performing a real British jazz classic - Stan Tracey’s Under Milk Wood suite from 1965. The eight numbers are woven together with text from Dylan Thomas’ groundbreaking soundscape conjuring up the Welsh fishing village of LLareggub. I am absolutely delighted that voice performer extraordinaire Pippa Evans will join us as narrator. Friday 15 August and Wednesay 20 August, 3pm, Scottish Arts Club. More details and tickets here.

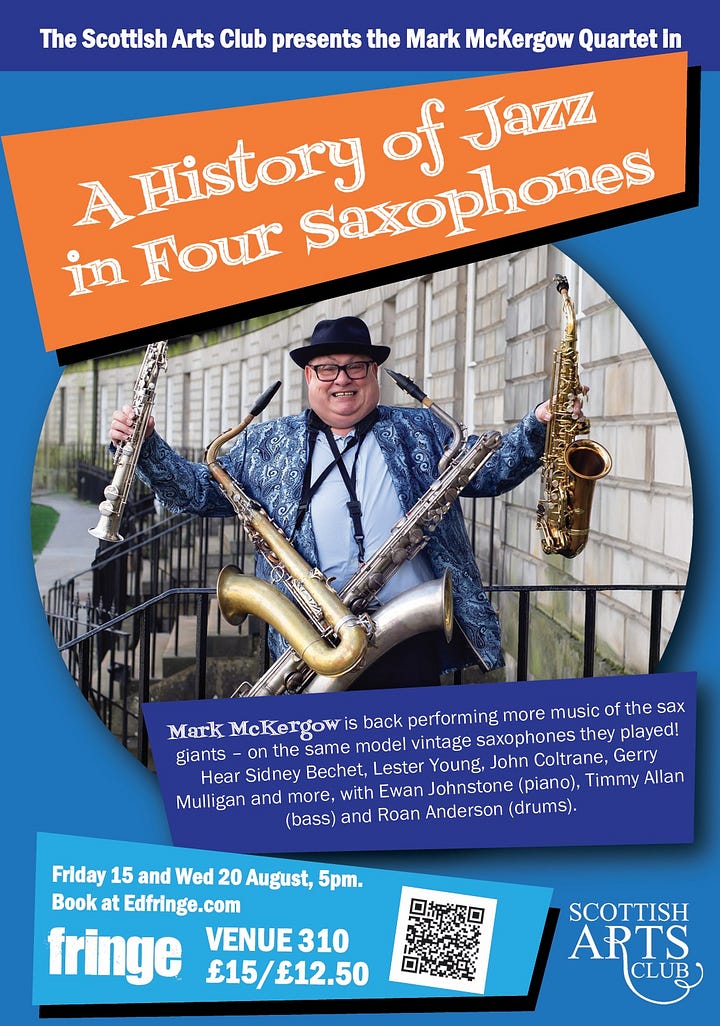

A History Of Jazz In Four Saxophones has me talking about the development of jazz and the saxophone, playing music of the jazz greats on the same types of instrument they used. There are different tunes for this year and we’ll be featuring Sidney Bechet, Lester Young, Charlie Parker, Gerry Mulligan and more. It’s a unique show, and once again I’m joined by my wonderful band of Ewan Johnstone (piano), Timmy Allan (double bass) and Roan Anderson (drums). Friday 15 August and Wednesday 20 August, 5pm, Scottish Arts Club. More details and tickets here.

Speed On The Seine

I’ve always been fascinated by speed records and record attempts ever since I was a fan of British speed aces Malcolm and Donald Campbell as a child. I’m a member of the Speed Record Club (SRC), and last year the editor of their Fast Facts magazine asked me to research some mysterious pictures he’d found online of aviation pioneer Louis Bleriot (the first person to fly the English Channel in 1909) with an odd-looking watercraft powered by an aero engine in 1912. It was great fun to research and I’m pleased to have pulled together a story which stretched from the late 19th century to the present day. It’s been published by the SRC and I am pleased to share it here (PDF download); something completely different to our usual material.

Better Decision Making with Solution Focused Coaching

This article was originally published in InterAction Volume 8 No 2 pages 7-19 (2016). It’s a bit of a classic and still well worth reading if you’re grappling with a difficult decision.

Abstract

This paper reviews different options for helping people faced with a difficult decision. This can be a particularly challenging context, where the standard solution focused (SF) approach of leaping into the future may not be instantly effective. Ten options for using SF methods to work with decision and dilemma situations are identified. Readers will not be short of possibilities when working with clients facing tough choices.

Introduction

When I am coaching managers or entrepreneurs, or even doing demonstration coaching sessions as part of trainings, one kind of question often appears as the topic. “I need to make a decision”.

This kind of situation has many forms. It might be “I’m facing a dilemma”, if there are two starkly different options. It might be “I need to choose between these options”. And following on from this starter is “I don’t feel ready, I don’t know what to do, I’m feeling stuck”.

In my early days of solution focused (SF) work, I might have been tempted to try to jump forward to a ‘better future’ after the decision. Use a Future Perfect or miracle question in the normal way – jumping forward to explore life after the decision or choice. However, there’s a problem with that; in order to answer that question, we already need to presuppose one choice or the other. And yet that’s exactly where the difficulty is lying.

This paper began life as a discussion at the SOLWorld 2016 conference in Liverpool, where Géry Derbier convened a conversation about using SF in decision making. I went along with an idea or two to share, and was very encouraged by the many possibilities which emerged. This paper is an attempt to set out as many options as possible for using SF work in coaching people towards difficult decisions.

Classical decision making

We make decisions all the time, and we don’t usually need SF coaching to help us. There are various ways in which we can help ourselves making decisions – these include:

Considering the options: Listing the possible options (and perhaps expanding the list to include previously unconsidered options)

Weighing up the pros and cons: Looking at the advantages and disadvantages of each possibility. Some people go as far as to make spreadsheets with scores, different weightings for various factors, and so on.

Talking it through with the others involved, or a neutral person: This is often a help in simply assessing where we are, and what’s important.

Paying attention to different kinds of signals: A good decision often ‘feels’ right as well as being logical or rational – and vice versa. Indeed, sometimes people come to me for coaching because the ‘logical’ decision doesn’t somehow feel right to them, and we can explore if they are missing something in the rational analysis (or indeed the feelings change with a better exploration of the logic).

Imagine making a decision one way – and see how that feels. I personally use a coin toss for this. Heads is option A, tails is option B, toss the coin and see if you feel pleased, disappointed, nervous or whatever – which gives you more information. It can be a surprisingly useful experiment.

These are the kinds of things we do all the time, and I would say that none of them makes particular use of SF ideas and tools. Remember the old adage that SF is not for any old ‘problem’, it’s for particularly stuck situations which we have already made the ‘usual’ efforts to resolve, and those efforts have been found not to be helpful. The three basic principles of SF work (ref) are

Don’t fix what isn’t broken

Find what works and do more of it

If it doesn’t work, stop it and do something different

Just having a bit of difficulty with a decision doesn’t qualify it as ‘broken’: this is just a part of life’s challenge. However, if we’ve done what we usually do to think through decisions and that’s not helping, then it might be time to bring some SF action into play. And, fortunately for us, there are many options.

SF decision making options

1. Focus on the time BEFORE the decision rather than the subsequent consequences

We can imagine the timeline of a decision between two options as flowing like this:

Rather than jumping into thinking about life after the decision (as with weighing up the pros and cons as discussed above), a useful strategy can be to look at the period between Now and the decision being made. (Note that this is not quite the same as the moment when the decision is acted upon… more about that towards the end of the paper.)

One way to do this is to use a simple scale of confidence.

“On a scale from 1-10 where 10 is very confident indeed, how confident are you right now of making the right decision?”

Suppose the person says ‘4’. Now you can proceed in the usual way with a scale:

“How come it’s a 4 and not a 3 or a 2? What’s helping you to be confident already? What else? What else?”

And then, having gathered as long a list as possible of what is helping them to be confident already:

“What would be the first tiny signs that your confidence had increased to a 5? What else?”

Note that here the platform, the topic of the coaching, is not the decision or its outcomes, it is the confidence of the person to make a good decision. This can often turn out to be a very fruitful line of conversation, not least because they have usually been struggling with the usual ‘pros and cons’ thinking and are delighted to find another track which nonetheless helps them to prepare for this decision.

Having established this scale of confidence in making the decision, it can then be used in various other ways:

“How high do you need to be, to make a sensible decision? What would be the first tiny signs you had reached that point? What difference would that make to you? To [significant others}?“

2. Disentangle elements of the decision

In some situations, it can become clear that there are several different aspects or elements of the decision. For example, when looking for a house to buy or rent, there are several competing elements: perhaps price, number of rooms, pleasant location, access to transport and so on.

This gives us the opportunity to create multiple scales, and work with them independently. On each scale, we can look at

What does 10 look like?

Where is this house/flat/whatever? How come it’s that high? What else?

What would be high enough on this scale?

What would be too low on this scale?

The important thing is not simply to name the number – “that house is a 7 for price but only a 3 for location” – but to explore how come it seems like that number, what makes it at this level, which parts of that seem particularly important, and so on. Another way to get into the same area might be to ask:

What needs to be in place for the decision to be made?

This then gives the possibility of including our next SF decision making tool…

3. Bring in the other people who are involved

If there is more than one person involved in the decision, it can be very important to engage the others – either directly, or in the conversation with the first person. If the different people can be gathered, this gives an excellent opportunity for the coach to have the kinds of conversations listed in section 2. above, engaging different viewpoints and priorities.

It can feel a bit difficult if different members of the group come to very different scaling values – but take heart! These are the times where some good explorations can reveal different understandings, perceptions and priorities, which is in itself a very useful step. Again, it’s important to look at the details behind the scaling numbers. Useful questions might include:

How come you think it’s a 7 and not lower? What else?

How come YOU think it’s a 3 and not lower? What else? What did the 7 person see that you didn’t?

Another strategy can be to include ‘silent scaling’. Set up a scale from 1-10 on a table or even on the floor. Get everyone to make cards with the different options, and then have them place them silently on the scale. Then have everyone observe the whole picture, still silently. Then perhaps have the people form pairs and discuss what they notice about where all the cards are sitting, and go from there.

4. Look at the benefits of a ‘perfect decision’

There is one way to look into the future in this kind of situation without presupposing the answer to the decision question. This is a process rather akin to a miracle question, and was first shown to me by my colleague Roy Marriott aka Shakya Kumara, who uses it in negotiations.

Suppose…. That you manage to make a perfect decision – for you, and for the other people involved… and afterwards, looking back, what would be the benefits of having made a perfect decision? Benefits to you? Benefits to the other people? What else?....

Note that this process does not actually require an answer of the form ‘A or B’: rather it goes beyond that, to look at why this is a decision in the first place. What are we trying to achieve? It can be very illuminating to explore this, and helps both to clarify the goals and aspirations around the decision, as well as getting valuable input and perspective from the others. Once again, you can use it either with the other people in the room, or at least it’s possible to tackle the question based on what you know about the wishes and desires of those involved.

5. Make the decision smaller

This is a classic piece of SF thinking. SF has been described (by me, at any rate) as combining big thinking (in terms of what’s hoped for) along with tiny thinking (in terms of details and small steps). If a decision is seeming difficult, then perhaps it’s too big. One way to address this is to look at how to make the decision smaller. A smaller decision will usually put less at stake, will be more exploratory than definitive and will be a step along the way to some further decision later on.

One way to make a decision smaller is to decide to take a step along the road, rather than go for the end of the road at the outset. This might look like doing more exploring, trying out a possible solution for a test period, gathering more data, etc. This can be more recoverable in the event of a mis-step, and allow further time before committing fully to one option or another.

Another possibility might be to ask questions like

Is it safe enough to try?

Is it good enough for now?

These come from the tradition of sociocracy (see for example Endenburg, 1998), an early form of non-hierarchical organisation and decision making. Various forms of sociocracy have been developed, including the more recent, highly-structured and somewhat controversial ‘Holacracy’ (Robertson, 2015). What these systems have in common is a desire to embrace and work with emerging change, rather than fighting against it or attempting (fruitlessly) to plan it out of existence.

So, if we can take a small test step as a prelude to a big step, why not do that? We get more information as a result of the test, we get to wait before raising the stakes, also we get things moving. ‘Is it good enough for now’ helps to combat the desire for perfection in data and implementation, to gold-plate the decision and make absolutely sure it’s correct (and usually by so doing miss the window of opportunity).

Another approach to decision making from the sociocracy traditions is:

6. Wait and gather more information

One of the elements of Holacracy I like is the emphasis on taking decisions at the ‘last responsible moment’. This is designed, of course, to allow better data gathering in fast moving and emerging situations. If one can wait, then why not? Of course, this doesn’t sit well with some macho type managers who see large decisions as more powerful, more heroic and (perhaps) less retractable later, thereby safeguarding their own legacies.

It’s important to note here that the ‘last responsible moment’ is not at all the same as the LAST moment. Waiting too long to take a decision can result in a rushed and confused last-minute gamble that is not properly thought through (even though it’s taken ages to get there). The last responsible moment has been defined by some (see for example Sironi, 2012) as:

…the instant in which the cost of the delay of a decision surpasses the benefit of delay; or the moment when failing to take a decision eliminates an important alternative.

This is not an entirely straightforward thing to judge, and indeed the concept has been criticised for not being rigorously applicable (Cockburn, 2011). However, the basic principle seems entirely appropriate in helping with difficult decisions. It’s rather like setting out on a family holiday involving a long drive from home to the seaside and the children wanting to know exactly what everyone will have for dinner when they arrive – it’s an open question, but not one that really needs to be answered now. I do not suggest that this option is routinely employed for everything – there are sometimes benefits to an early decision, and postponing everything may be a recipe for uncertainty and strategic drift. However, in tough situations this can be a useful principle.

7. Use the SOAR framework

While waiting for the last responsible moment, one useful framework to gather data comes from the world of Appreciative Inquiry (Ai). SOAR was developed as a more resource-based alternative to the famous SWOT strategic planning format. SWOT stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats, and was used from the 1960s as the basis for surveying both an organisation and its environment. Readers of this journal will recognise that both weaknesses and threats are not the most SF or appreciative way to look at things, and so an alternative framework was developed.

SOAR was first envisaged by Stavros, Cooperrider and Kelley (2003). There are different versions; the one I prefer to use is

Strengths

Opportunities

Aspirations

Resources

The first two of these are carried over from the earlier SWOT method. ‘Aspirations’ is coming from a very different place – SWOT says nothing at all about what an organisation wants. Rather, it was intended to act as a backdrop for the organisation deciding what it ought to do, based on its competences and environment. In SF, the desired future plays a key role and therefore incorporating Aspirations feels like a very natural step. The R in SOAR is sometimes (as in Stavros, Cooperrider and Kelley above) standing for Results: how will we know we are moving forward. This is fine, but I prefer R for Resources. Looking at what we have that’s available to use in moving forward seems like a gap in the other three aspects. In particular for decision making, a look at the resources available to help (and perhaps also obtainable as well as on-the-shelf) could make a worthwhile difference.

8. Look for ‘what works’

One key element of SF practice is to look at what’s worked before in similar situations. This definitely applies to making decisions. So:

How have we made similar (and successful) decisions before?

I remember coaching someone who was having difficulty finding the right school for their son. I tried various lines of inquiry, but the session came to a remarkable close when I asked “When have you made similar decisions before?”. The client thought briefly before saying “Choosing our house….. oh yes!”. In about ten seconds she had put together the house-buying strategy with the school finding strategy, arrived at a new answer she was confident in, and that was that.

Another way to include ‘what works’ is to see which of the possibilities is most based on what we are doing at the moment (and therefore perhaps most likely to work in the way we think it will). Building on known ground is likely to be more firmly rooted than totally new ideas. This of not always a prime factor, but in a tight spot it might make a useful difference.

9. Find new options

In dilemma situations, one of the aspects which makes life difficult is that the choice appears to be between two options – neither of which look terribly appealing. So, looking to expand the choice is always going to be an interesting possibility. One way to do this is the tetralemma form.

Deriving from Indian and Buddhist logic, the tetralemma show that for a given proposition X there are not two possibilities (X or not-X), but rather four:

X (affirmation)

Not-X (negation)

X and not-X (both)

Neither X nor not-X (neither)

Whereas the first two possibilities are the usual ‘horns of the dilemma’, the original options, the tetralemma opens up two further possibilities – both and neither. Of course, the usefulness lies not so much in the logical concept as the exploration of what these terms mean in the actual context. How could we manage to have ‘both’? What might it mean to have do ‘neither’? What does this open up? So, to take a possible simple example: Moving house to another city.

X – move house

Not-X – don’t move house

Both – rent somewhere in the new city to see if you like it while keeping the original house (and other options too)

Neither – move somewhere completely different

10. Ban yourself from making the decision now

This is a rather paradoxical option. In the early days of Steve de Shazer’s practice he was fond(?) of sometimes using paradoxical interventions, where the client is told to deliberately act to create the symptom they are struggling with. So, for example, someone with a fear of failure is told to deliberately fail at something. This type of intervention is not really a part of modern SF practice, but it can serve to open up new possibilities in interesting ways if all else fails.

So, in the case of a difficult decision, one option might be to agree that the client will STOP trying to make the decision or even think about it for a period – perhaps a week or a month. Having driven themselves to distraction by worrying about this decision, desisting from the strife and anxiety might easily have an affect in freeing things up and perhaps introducing new options. Or, it might have the effect of making the person realise that they are actually keen to take the decision and now know which way they want to turn. Whatever, this is always an option to ‘do something different’ if nothing else seems to be working.

11. And finally – you can change your mind

At the beginning of this article I presented a diagram showing the time flow of a decision from preparing to make it, making it and then acting on it. It is worth remembering that having ‘made’ the decision, there is usually some period where it has not yet been acted upon (at least, not irreversibly so). One of the key principles of SF is that ‘change is happening all the time’ (Jackson & McKergow, 2007). What looks like a sensible decision can quickly shift to looking not very sensible at all – either in the light of changing events or even personal reflection on being faced with the reality of the situation.

Working in an SF way we look to embrace and engage useful change. This can ultimately mean changing our minds. There is a certain macho element which prefers to stick with a poor decision rather than change it – but that can look like dogged determination rather than skilful and agile flexibility. There is an old saying that ‘if I knew then what I know now…’ (then I would have acted differently then). But guess what… you DO know now what you know now! So act on it – even if you didn’t know it yesterday.

Conclusions

This paper has touched on ten different ways to use SF ideas in helping our clients make better decisions. Far from being the hard-to-reach scenario we feared, there are many ways in which SF coaches and consultants can be useful resources to our clients without actually telling them what to decide. That, of course, is for them.

References

Cockburn, A. (2011). Last Responsible Moment reconsidered. Retrieved from http://alistair.cockburn.us/Last+Responsible+Moment+reconsidered, 22 November 2016

Endenburg, G. (1998). Sociocracy: The organization of decision-making 'no objection' as the principle of sociocracy. Delft: Ebuuron.

Jackson, P. Z. and McKergow, M. (2007). The Solutions Focus: Making Coaching & Change SIMPLE. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing (second edition)

Robertson, B. (2015). Holacracy: The Revolutionary Management System that Abolishes Hierarchy. London: Penguin

Sironi, G. (2012). Lean Tools: The Last Responsible Moment. Retrieved from https://dzone.com/articles/lean-tools-last-responsible.

Stavros, J., Cooperrider, D., & Kelley, D. L. (2003). Strategic inquiry appreciative intent: inspiration to SOAR, a new framework for strategic planning. AI Practitioner. November, 10-17.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Géry Derbier for convening the original discussion about SF and decision making at SOLWorld 2016, and for providing his flipcharts as the initial basis for the article.