27. Is it time for a deep breath moment?

The difference between small adaptive changes and a change in hopes, goals and direction

I have written here before about dynamic steering and the importance (as I see it in both Solutions Focus and Host Leadership) of making small adjustments all the time, while moving in the direction of a long-term hope or goal. It came up specifically in my piece on the Bicycle theory of change (the importance of keeping moving rather than stopping) and also the Death Of Resistance article, where the importance of building co-operation by making adjustments was to the fore.

Making small adjustments sounds like common sense, but it’s anathema to the ‘plan and deliver’ school of thought were everything is supposed to be considered at the outset, and a change (any change) of plan shows you failed to plan properly. Fortunately, this outlook is much less prevalent that it used to be. It turns out to be an excellent response to the inevitable changes that emerge over time; we now know from complexity theory that outside very simple tasks it’s impossible to consider everything at the outset, as there will always be small differences which will turn out unexpectedly to make a difference.

But what happens when you have been making small adjustments, or feeling stuck, or just not making the hoped-for progress? Perhaps it’s time for a deep breath moment – time to adjust not simply the small changes but the hope, direction or goal itself?

The User’s Guide To The Future

I introduced the User’s Guide To The Future framework in the book Host (McKergow and Bailey, 2014). It’s an extension of pieces of Solutions Focus put together in a usable way and it will help us here. Basically, not all the different elements of the future are of equal usefulness to us right now.

The far future, the horizon, is very useful indeed. What are our hopes, dreams and aspirations? What would we like to move towards? What version of the future draws us forward? This is a wide open question, and one that is fundamental is helping move forwards. As someone once said, if we don’t know where we want to go, then any road is fine. The way that Solutions Focus uses this as the starting point was in its day revolutionary; before Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg, most therapies started off by examining problems, their causes and (worse still) their ‘root causes’. As our friends at BRIEF in London say, taxi drivers ask “where do you want to go?”, not “where have you come from?” to get things moving. SF is the same.

Then we have just before the horizon – what needs to be in place for the hopes and aspirations to happen? Some people call this ‘back-casting’, and it’s a very useful way to expand on the desired future. There’s a good example in Miles Shepheard’s case about the fruit farmers of Australia vs the flying fox population in The Solutions Focus book, second edition (2007 – with the purple cover). This is about finding ‘building blocks’, things that will have to be in place that will be key components. In the flying foxes case, farmers wanted a humane and effective way of controlling the pest population. Among the building blocks were a proper research programme, a flying fox conservation and management plan, and strong partnerships between the various stakeholders.

Moving from right to left, we now have the most distinctive feature of the User’s Guide – ‘Ant Country’. This is the middle distance of the future, and it turns out to be the least useful zone. It’s not far enough into the future to be interesting in terms of direction, and too far away to be useful in terms of the next steps. It feels important – surely there should be a plan for this – but actually it’s a distraction. When we tackle something that’s complex with many inter-related elements, there is no way to plan the whole thing, in detail, at the outset. So pass over Ant Country. (I’ll come back to the name and how it was conjured up another time.)

Moving again to the left, we now have the near future (tiny signs of progress) and the very near future (small next steps). This is where the dynamic steering and adjustments usually happen. We know what would constitute tiny signs of progress – what to look out for – and then take small actions to move towards those. Things happen, sometime the signs of progress appear (which is encouraging) and other times they don’t (that’s good learning). In the latter case a rethink is required, by adjusting progress indicators and actions. So far, so good.

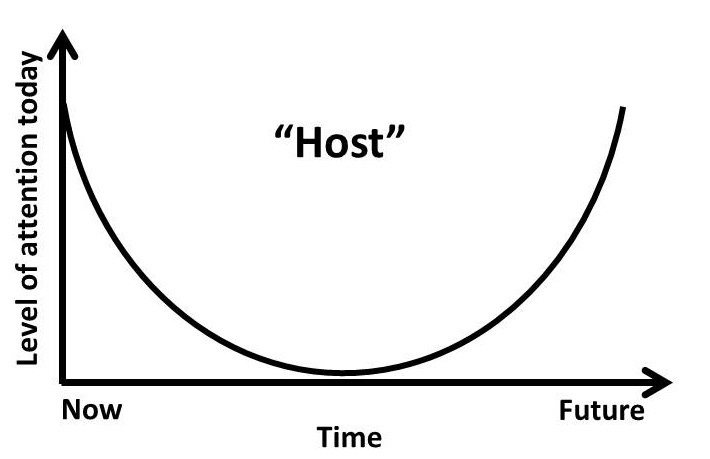

So in terms of where to put our attention, the far future and the near future are valuable and the middle future is NOT. That’s the attention profile of the host leader (and indeed the SF coach – Peter Röhrig and I introduced the User’s Guide as a coaching framework at the SOLWorld 2019 conference and wrote up an article which you can read).

The deep breath moment

This dynamic steering and adjustment is fine… until, sometimes, a more fundamental adjustment is called for. I call this a ‘deep breath moment’. It’s the time when the far future is re-examined, hopes and aspirations are revised, and a new direction is set.

I’ve experienced this several times in my life and work. What surprises me is that it can creep up without being noticed and appear suddenly, a realisation that something needs to change. Other times it can be a dawning realisation, something that starts as a quiet idea, keeps coming back and seems to get louder and louder until it’s inescapable. But when you do a re-set, a revision of hopes and set a new direction, the effect can be dramatic. Often previously stuck things start to move quite quickly – like pushing on the (push) door when you’ve been fruitlessly pulling and getting nowhere. Things fall into place in different ways. New connections get made. New possibilities arrive. And what was a frustrating stuckness becomes once again a moving and flowing process.

The first thing to say is that this is not a sign of bad planning. On the contrary; it’s a sign that the User’s Guide to the Future is being used well. One of the wonders of viewing the world as emergent is to acknowledge that the unexpected will sometimes happen, and that’s just how it is. The key thing is not to totally prevent the unexpected (which would be futile) but to respond to it well and to use it constructively.

Sir Chris Bonington – awareness on Everest

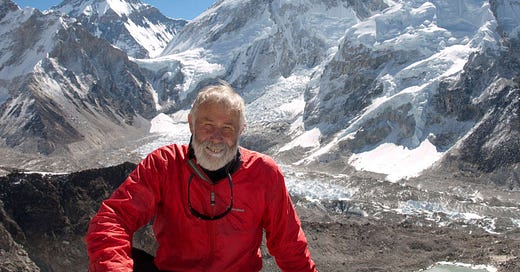

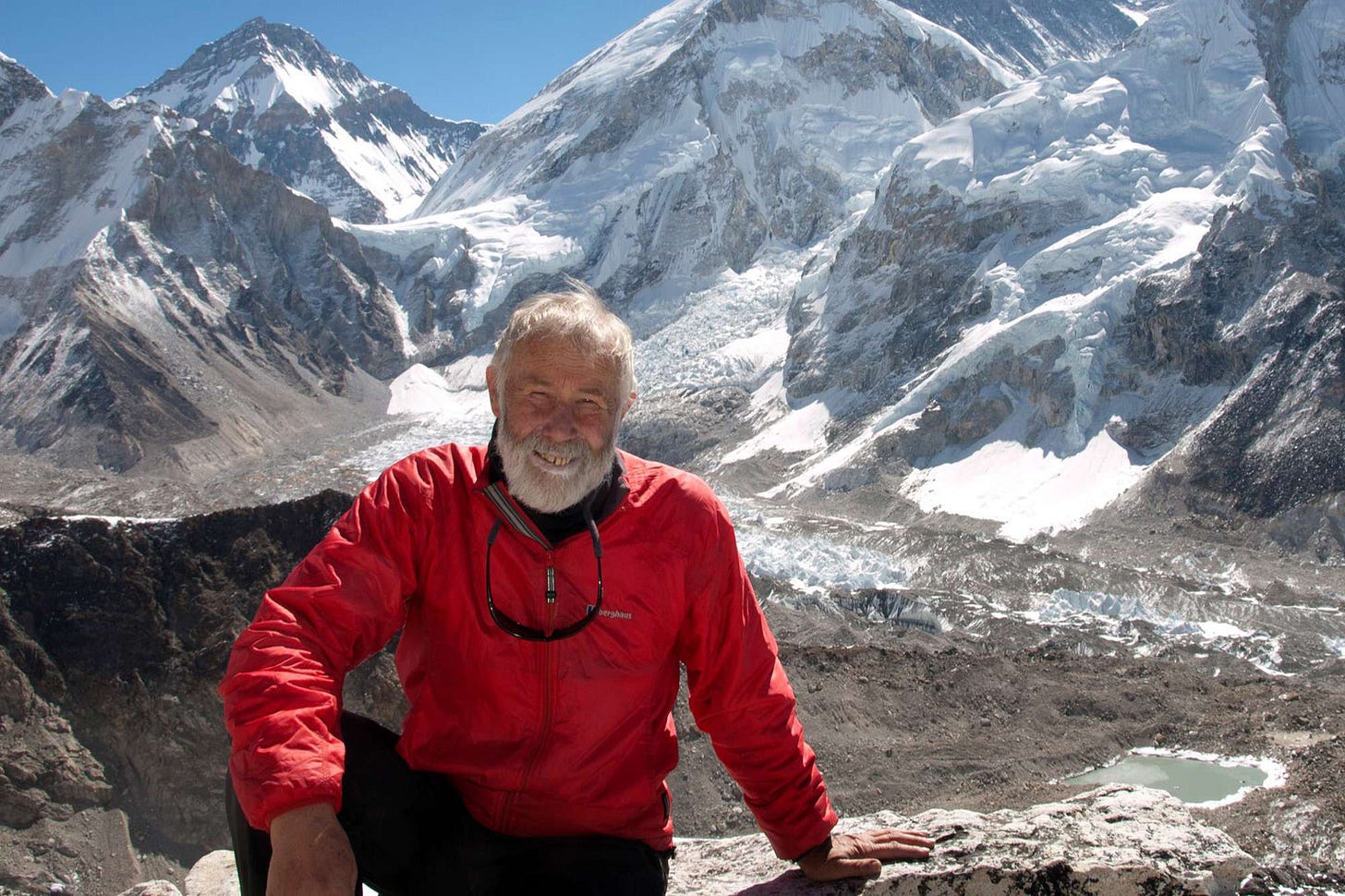

As part of writing the Host book, Helen Bailey and I interviewed a number of leaders who we thought acted like hosts, and hosts who acted like leaders. One of the people I was most excited to meet was mountaineer Sir Chris Bonington, whose books I had read decades before when he was leading expeditions like the South West face of Chomolungma/Everest, described by him as ‘Everest – The Hard Way’. Helen was using Chris as a guest speaker on her coaching programmes (along with me and Olympic gold medallist cyclist Chris Boardman – that’s a list of three people on which I never expected to feature!) and so we were able to meet him at his remote Lakeland home.

We started the interview and Chris summed up the need for responsiveness very well, saying:

“The clear vision is important – then you keep pressing on, or indecision takes place. Of course, you have to be prepared to change plans – it’s a balance. Be inflexible and drive on into trouble, be a ditherer and get nowhere. You have to get the balance right.”

Chris told us of his experience leading an expedition to the South West face of Mount Everest in 1975. This route was very much “the hard way” to ascend the world’s highest peak – five expeditions had already tried and failed, including one led by Bonington in 1972. The climb had broadly gone well, and Bonington was enjoying taking his turn out at the front, forging the route. (Ascents on great peaks such as Everest involve groups of climbers taking turns to make the route, descend to a lower camp to rest and acclimatise to the altitude, and then carry supplies up to their colleagues.) It seemed as if the expedition might succeed way beyond expectations. Then, in conversation with expedition doctor Charlie Clarke, came a deep breath moment. Bonington recalled:

“I had been at 8000 m altitude for ten days. I’d planned out a third summit bid (as well as the two already planned) with bigger groups and myself taking part in the third summit bid, so we could double the number of people getting to the summit, not for a record but so that as many people as possible could enjoy the satisfaction – it was technically feasible. I was fine. Then Charlie pointed out over the walky-talky that I would have had to have stayed for another five days – which would have been too much. AND there were a lot of unhappy climbers at the bottom who had not been included in the summit bids. I was on the radio to them, but it’s a terse medium . . . I had been at the right place [high up] at Camp 5 supervising and taking part in the push through the Rock Band. Once I had nominated the summit bids, there was nothing more for me to do there. So, nominating someone else for the third summit bid and going back down to help sort things at Advance Base was the right thing . . .”

The expedition succeeded in getting Doug Scott and Dougal Haston to the summit in the first bid, and Peter Boardman and Pertemba Sherpa in the second, albeit with the loss of climbing cameraman Mick Burke who disappeared after pushing on alone during the second summit ascent. This was the second of Bonington’s three expeditions to Everest as leader. He did not make the summit himself on any of these. He did finally succeed in making it to the top –as a “guest” and logistics planner on Norwegian Arne Naess’s 1985 expedition, rather than as the host of his own efforts. (from Host, McKergow and Bailey 2014, pp 93-94)

As our conversation continued, Chris warmed to the idea of host leadership. I was delighted, of course. Here was someone who absolutely acted as host to his expeditions, literally inviting colleagues to join him, providing logistics and supplies, co-ordinating, using the resources of the entire team and knowing when he had to put the success of the team ahead of his own desires. I bitterly regret that I didn’t have the wit to take a selfie of the three of us (Chris, Helen and me) together.

When is it time for a deep breath?

It’s hard for me to be definitive about when a deep breath moment is needed. I’ve had a few deep breath moments over the years; leaving my secure job in the nuclear industry to become an independent consultant, ceasing involvement with UltraSound, the contemporary jazz orchestra I ran in the 1990s, changing the people I worked with, moving to Scotland in 2016, to name a few. Some initial thoughts based on my own experience:

When you’re totally fed up

When you’re tried various things to no avail

When there is uncertainty within your team/organisation (as was the case for Chris Bonington)

When things are drifting

When priorities elsewhere change (which might be an opportunity)

When an unexpected external event arrives and throws everything up in the air.

And it might still pay to wait a moment. The night is darkest before the dawn, it is said. And knowing that a deep breath moment is not only possible but within reach may help the night to pass more quickly.

When I am teaching SF coaching (as outlined in The Solutions Focus book), I advocate starting with the Platform (what do you want?) and then progressing from there. I tell learners that if everything starts to get confusing, messy and intractable, that’s a good moment to go back to the Platform. It may have changed slightly, it may change a lot, it may need clarifying or at least reminding the coachee about what we’re doing. Going back to the Platform is a form of deep breath moment.

After the deep breath…

Fortunately the Users Guide framework is as useful as it ever was, and can be worked through again with the new hope/aspiration. Try it now. Draw the five zones on a piece of paper (or make a slide) and start filling it in – working from the right (horizon) to the left (small next steps) and missing out Ant Country. I’ve had coaching clients spend half an hour on this and feel they’ve reclaimed control of their lives – stress reduces, things clarify, priorities line up.

Reference

McKergow, M. and Bailey, H. (2014). Host: Six new rules roles of engagement for teams, organizations, communities and movements. Solutions Books. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Host-Mark-McKergow/dp/0954974980/

Dates and mates

Helen Bailey worked with me on pulling together the many perspectives which make up the Host Leadership metaphor and model. She is still working as a coach and consultant from her wonderful converted mill house (now with added meditation suite) near Cartmel in the south Lake district, working mostly with professional firms like accountants and lawyers. She and husband Jack adopted a son a few years ago, which keeps them busy!

A big thanks to my friend Chris Corrigan for quickly picking up on this article and adding his own thoughts about 'Ant Country' and how to prepare for it. Very well worth a read https://www.chriscorrigan.com/parkinglot/time-and-affordances-and-a-deep-breath/

I really enjoy The Users Guide To The Future. It helps me navigate the work with "Long-short goals", time perspective, attention and presence. This week, the working group and I had space and time for a deep breath moment and to reflect as we did some wonderful reflection walks with inspiration from the nature, art and buildings in the area we visited.

It resulted in thoughts and nice conversations about the group, about the work and about joy. Things that groups sometimes need to talk about to develop.