68. Missions vs goals: Better ways to tackle grand challenges and wicked problems?

Keir Starmer’s Labour government is promising to be ‘mission-led’. What does that mean and how might it connect with Solution Focus?

Following the July 2024 General Election, we have a new government and a new prime minister in the UK. Sir Keir Starmer, knighted for his previous work as director of public prosecutions, leads a Labour administration with a large majority, meaning he can probably get things done. What is he hoping to do?

In 2023 Starmer announced boldly that he wished to preside over a ‘mission-led’ programme. This sounds a bit flim-flam on first hearing, but it more interesting than it sounds. There is a serious body of thinking around how working with ‘missions’ can help unstuck progress and get around tough problems in tackling major changes. This time I’ll take a look at what it means, how it might work and what to look out for in the weeks and months ahead.

What is a mission?

Keir Starmer’s missions for government have been derived in tune with the work of economist Mariana Mazzucato whose 2021 book Mission Economy: A moonshot guide to changing capitalism has been making waves in public and private sectors alike. The book says:

Taking her inspiration from the ‘moonshot’ programmes which successfully coordinated public and private sectors on a massive scale, Mazzucato calls for the same level of boldness and experimentation to be applied to the biggest problems of our time.

Mission Economy looks at the grand challenges facing us in a radically new way, arguing that we must rethink the capacities and role of government within the economy and society, and above all recover a sense of public purpose.

To solve the massive crises facing us, we must be innovative — we must use collaborative, mission-oriented thinking while also bringing a stakeholder view of public private partnerships which means not only taking risks together but also sharing the rewards. We need to think bigger and mobilize our resources in a way that is as bold as inspirational as the moon landing—this time to the most ‘wicked’ social problems of our time.

We can only begin to find answers if we fundamentally restructure capitalism to make it inclusive, sustainable, and driven by innovation that tackles concrete problems. That means changing government tools and culture, creating new markers of corporate governance, and ensuring that corporations, society, and the government coalesce to share a common goal.

Mazzucato writes that the archetypal example of a mission is the USA’s moon landing prorgramme of the 1960s. When President John F Kennedy made his famous pledge on 12 September 1961 at Rice University to that the US ‘before this decade is out, land a man on the moon and return him safely to the earth’. At this point the US was well behind the Soviet Union in the ‘space race’ – they had yet to even launch man into orbit. However, Kennedy saw the opportunity (and also perhaps the geo-political risk) of seizing the opportunity of space. As we know, the USA succeeded in landing Apollo 11 on the moon in July 1969.

What’s the difference between a mission and a normal goal/plan?

Mazzucato characterises a mission with six attributes:

Vision infused with a strong sense of purpose;

Risk-taking and innovation;

Organizational dynamism;

Collaboration and spillovers across multiple sectors;

Long-term horizons and budgeting that focused on outcomes; and

A dynamic partnership between the public and private sectors.

It seems to me that the key difference between a mission and a normal goal and plan is that in the former nobody knows, at the outset, how to do it. The process is one of widescale engagement combined with innovation, with a long-term focus. With the more normal goal and plan, there is already a route in mind and it’s more or less a case of doing what we know how to do already. (This does not mean that there are not unexpected challenges along the way! Far from it.)

Links from missions to Solution Focus

My work in bringing the Solution Focus (SF) approach has a lot of parallels with mission-based thinking. Firstly, in both cases we embark on the process in a spirit of experimentation and exploration. Progress is built a step at a time. One thing leads to another, and change can ripple out across different domains of life. There’s a choice at the start that this thing is worth pursuing. And creating some kind of description of how things might be when it’s all working better can illuminate and inspire.

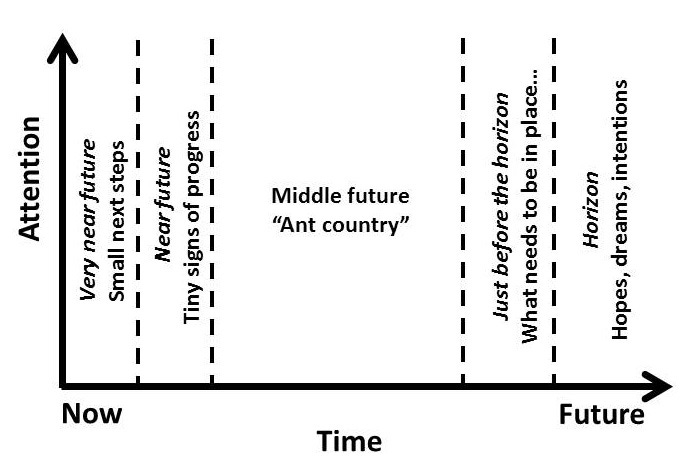

I have written here before about the Users Guide To The Future framework which I think is particularly relevant to mission-based work. This brings a focus to both the long-term hopes and aspirations, and also the very short-term signs of progress and next steps. The key element is to focus on these and to ignore ‘Ant Country’, the bit in the middle where it’s too complex to plan (yet) and not far enough along to be useful.

One key similarity between the User’s Guide and the moon mission is that the USA used the ‘just before the horizon’ zone very effectively. In thinking about what needed to be in place for the moon landing, they realised they had a choice of four basic strategies:

Direct ascent – fly a rocket direct to the moon and land

Earth orbit rendezvous – build a craft from parts close to the earth and then fly it out

Lunar surface rendezvous – first fly and unmanned craft, then follow up

Lunar orbit rendezvous – fly a two-part ship to the moon’s orbit, where the lander separates and lands.

It was the last of these that won out and proved successful. This early choice was important in narrowing down what would be required and focusing the different suppliers and designers on something coherent. Had the Americans not made this choice, the risk would be that all four approaches would be developed with consequent huge waste of resource and effort. One key to success was developing ways for two spacecraft to ‘dock’, connect to each other while flying in orbit; the US Gemini project of the mid 1960s had a clear focus on this.

Keir Starmer’s missions

The prime minister has announced five missions which would be at the heart of his time in office:

1) Kickstart economic growth

to secure the highest sustained growth in the G7 – with good jobs and productivity growth in every part of the country making everyone, not just a few, better off.

2) Make Britain a clean energy superpower

to cut bills, create jobs and deliver security with cheaper, zero-carbon electricity by 2030, accelerating to net zero.

3) Take back our streets

by halving serious violent crime and raising confidence in the police and criminal justice system to its highest levels.

4) Break down barriers to opportunity

by reforming our childcare and education systems, to make sure there is no class ceiling on the ambitions of young people in Britain.

5) Build an NHS fit for the future

that is there when people need it; with fewer lives lost to the biggest killers; in a fairer Britain, where everyone lives well for longer.

These are of course high-level and use somewhat abstract language, but they sound good to me. The question, of course, is whether Labour can take them from good-on-paper into actual action. In their first three months, the government have given priority to dire warnings about how the dreadful financial situation they inherited from the Conservatives. This is not boding well – missions need funds, particularly at the outset when uncertainty is high and innovation is needed. However, let’s see what might be clues that the missions are actually getting into action.

Signs that the mission-led way might be starting to work

Here are my five signs that things might be getting underway. The Government is seen to be starting to:

Engage widely (including across the political spectrum as well as with different sectors). The point about missions is to draw people together.

Work across departments in government and the civil service, led by experts with ministerial clout (I draw this from Sam Freedman’s post excellent post on Comment Is Freed, here on Substack).

Get people excited, get community involvement. The country is gasping for something to hope for and some positive news.

Making some early choices – in the same way that Apollo chose the lunar orbit rendezvous approach. This will focus efforts and produce initial coherence.

Encourage and underwrite innovation. We need to explore, try, innovate and pilot, not get bogged down for lack of support.

These would all be excellent small signs that progress was starting and that the (very good) idea of working in a mission-based way was starting to have an impact. We’ll see…

Conclusions

Solution Focused work involved embracing the unknown and the natural complexity of the world in seeking to explore ways towards much better futures. It’s exciting to see the same kind of spirit appearing in mission-based approaches at the top of government. And, of course, any organisation which embraces these ways to engaging people towards a new and developing future is well on the way to being both effective and humane.

Dates and mates

Sunday 27 October 2024: My flagship SF Business Professional course starts with the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. 16 weeks of learning, interacting, practicing, a project and the best possible grounding in SF work in organisations. Accessible everywhere in the world! Small group, lots of connection, a wonderful experience. I won’t be running many more of these so take the chance now.

Comment Is Freed is the UK’s most widely read political commentary Substack. Sam Freedman, a senior fellow at the Institute for Government, has experience inside Government as well as with think-tanks and writes mainly about UK politics and policy. His father Lawrence, Emeritus Professor of War Studies at King’s College London, writes about foreign affairs and often takes a historical perspective on emerging developments. Together they are a great team, publishing at least three free long pieces a month (and more if you pay the modest subscription).